10.5 Compute, interpret and compare return on investment (ROI) and residual income.

Rina Dhillon

Return on Investment (ROI)

As explained earlier, an important characteristic of an investment centre is that the manager can control or significantly influence the investment funds available for use. Thus the main basis for evaluating the performance of a manager of an investment centre is return on investment (hereafter ROI). ROI measures the rate of return generated by an investment centre’s assets. ROI is the ratio of operating income to average operating assets. Operating income is calculated as earnings before interest and taxes (EBIT). Interest and taxes are typically omitted from the measure of income in the ROI calculation because they may not be controllable by the manager of the segment being evaluated. Operating assets typically includes all assets used in the production of goods or services such as cash, accounts receivable, inventory, and the property, plant and equipment.

When we want to evaluate an entire business’ performance, all assets would be included because owners want to evaluate their return based on the entire investment. However when evaluating the performance of a sub-unit, any assets included must be under the control of the managers being evaluated. The average of begiining and ending operating assets is calculated for two key reasons: (1) ROI is intended to capture operations over time, not just at the end of the time period; and (2) ROI could be manipulated by temporarily reducing investment at the time performance is measured.

The calculation of ROI is generally broken down into two components that provide additional information about performance – a measure of operating performance (called margin, i.e. profit that is earned on each dollar of sales) and a measure of how effectively assets are used during a period (called asset turnover; i.e. sales that is generated for a given level of assets). This decomposition of ROI into margin and asset turnover is often referred to as the DuPont Analysis which recognised that the performance of an investment centre must consider the level of investment along with the profit generated from that investment.

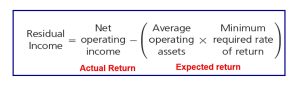

The formula for ROI is as follows:

As the above diagram indicates, the calculation for return on investment can be simplified as net operating income divided by average operating assets. Let’s now look at an example of applying ROI.

Entertainment Games Company has two separate but related divisions in their computer games segment: digital video and analog video. The digital video division has sales of $900000, net operating profit of $150000 and average operating assets of $1 million. Calculate the ROI for the digital division.

ROI = (Net operating income/Average operating assets) = $150000/$1000000 = 15%

Residual Income (RI)

As an alternative to ROI, the manager of an investment centre can be evaluated on the basis of the residual income (hereafter RI) generated by the investment centre. RI is the amount of income earned (actual return) in excess of a predetermined minimum rate of return on assets (expected return). Residual income is calculated as net operating income minus the product of average operating assets times the minimum required rate of return:

Essentially RI measures the dollar amount of profits in excess of a required rate of return (commonly referred to as capital charge which is usually set my management). Many businesses set a minimum return expectation for operations and new investments. RI takes this expected return into consideration. The size of investment affects RI less than ROI because it is used only to value the dollar amount of expected return, not as a denominator like ROI. All other things being equal, the higher the residual income of an investment centre, the better.

Let’s return to Entertainment Games Company to see how RI is applied in evaluating investments.

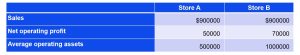

Entertainment Games Company is trying to determine which of the two gaming stores would be a more beneficial investment. The minimum required rate of return is 7 per cent and the following information about the two gaming stores have been collected:

Calculate the residual income for each store and determine which is a better investment.

Store A Residual Income: $50 000 – (500000 x 7%) = $15 000

Store B Residual Income: $70 000 – (1000000 x 7%) = $0

While the residual income of Store A is higher than that of Store B, and since the stores have different levels of operating assets, it is misleading to compare the two amounts. We would need to calculate the ROI to get a better picture:

ROI Store A: ($50000/$500000) = 10%

ROI Store B: ($70000/$1000000) = 7%

Store A is a better investment as it has a higher ROI. It is also important to note that if your ROI equals your desired return, then your residual income is 0 (as observed for Store B). This means that you earned a profit equal to what was expected, so you did not over-deliver or under-deliver – hence zero residual income!

Comparing ROI and RI – Advantages and Disadvantages

A division’s ROI is easily compared with internal and external benchmarks and with other divisions’ ROI. By holding managers responsible for some level of ROI, it reduces the tendency of managers to overinvest (as mentioned above, average operating assets is the denominator in the formula so the bigger the investment, the lower the ROI assuming the same profits) in projects. ROI also encourages and motivates managers to increase sales, decrease costs (factors affecting numerator component) and minimise asset investments (factor affecting denominator component).

However, ROI also discourages managers from investing in projects that reduce the division’s ROI, even though they might improve the ROI of the overall business. For example, if the current ROI at a facility is 25 per cent and a manager is evaluated on this measure, they may reject potential projects/investments that would be profitable but lower the location’s overall ROI. Let’s assume a manager has achieved an ROI of 25% using $5 million in assets in an existing project. If they invest $5 million in a new project with an ROI of 15%, the average ROI will become 20% [(25+15)/2)]. As a result, the manager would rather not invest in the new project even though the 15% is an acceptable return.

Using RI here would avoid this problem. Using RI, a manager with a required rate of return of 10% would accept the new projects as it increases the overall residual income by $250000 [(15% – 10%) * $5 million]. Even though the investment reduces the division’s ROI, the company will lose out on $250000 if the project is not undertaken.

RI is also not without its disadvantages. In some cases, evaluating the performance of an investment centre and its manager using RI can cause problems. Since residual income is an absolute measure (dollar value), it should not be used to compare the performance of investment centres of different sizes. Larger sub-units are more likely to have larger residual income and thus residual income is more useful as a performance measure for a single investment centre. Given ROI is independent of size, it is better suited as a comparative measure of performance across sub-units.

Despite these limitations, businesses still use ROI and RI to assist with the evaluation of divisional performance. We have so far focused our attention on financial performance measures. In the next section, we briefly explore the balanced scorecard which provides the use of multiple measures – both financial and non-financial – in combination to measure performance.