11.1 Understand the role of management accounting in documenting sustainability practices

Leanne Gaul and Rina Dhillon

In 1987 the World Commission on Environment and Development released a report titled Our Common Future[1] which explored issues over climate change. This culminated in a call for action to combat accelerating environmental deterioration and adverse social impacts. It gave rise to the concept of sustainable development which “meets the needs of the present without compromising the ability of future generations to meet their own needs”.[2] This definition indicates the importance of present generations meeting their own needs in a manner that does not impair future generations entitlement to the same, ensuring a balance between economic growth, environmental care and social well-being. This was the first time future generations were considered as stakeholders. Authors of the Our Common Future report indicated a need for technology and social organisation to be managed and enhanced for the benefit of all stakeholders both in the present and future. Sustainability can be maintained at a certain rate or level, as in sustainable economic growth, and can also be upheld or defended, as in sustainable definitions of good corporate practice, i.e. sustainability practices. As businesses derive profit from the environment and society, and has society as its ‘market’, the environment, society and businesses are interconnected. This link between business, society and the environment is also represented in the Sustainable Development Goals (SDG) ‘Wedding Cake’, depicted below, where the biosphere is the foundation of economies and societies, adopting an integrated view of social, economic, and environmental development:

From a global context to the Australian experience, escalating natural disasters such as bush fires (Black summer 2019-2020[3]) and flooding have resulted in citizens calling out for accountable leadership in the mitigation and prevention of climate change and related events.[4] The Australian community at large is a consumer of goods and services and increasingly are making purchase choices based upon the sustainability practices of associated firms, which is progressively being recognised by organisations today.[5] In recognising the importance of sustainability, from both a business and consumer context, it is critical to define what it actually means. Escalating demands for greater direction have led to numerous influencers in the sustainability field, but to pinpoint a specific origination point for world-wide recognition this would coincide with the publication of the Our Common Future report in 1987.[6] From this time the concept of sustainability, sustainable development and sustainability reporting have been iteratively developed and, like the changing nature of the worlds ecosystems from the impacts of climate change, these living concepts will continue to develop and mature.

A widely recognised contributor to the sustainability reporting field was a British corporate environmentalist by the name of John Elkington[7] who introduced the concept of Triple Bottom Line (TBL) reporting in his seminal article “Accounting for the triple bottom line”.[8] He conceived the idea that reporting should incorporate not only economic or financial information but also environmental and social disclosures.[9] Financial reporting includes the traditional accounting disclosures; Balance Sheet, Income Statement, Cash Flow Statement, Statement of Changes in Equity, and associated notes. Environmental reporting reflects an organisation’s accountability over impacts of its operations on natural capital such as the extraction and use of environmental resources, the creation of by-products such as carbon emissions and any consequential damage to flora and fauna. This may be offset by the use of renewables or environmental remediation.[10] The social bottom line is associated with social capital which can be connected to inflows and outflows to the organisation, such as community philanthropy, improved working conditions and so on.[11] The incorporation of economic, environmental and social accounting can also be transactional, inflows, outflows, debits and credits, hence the integration of these three capitals into one report informs its user of not only the financial outcomes, but its environmental and social performance.[12] This has implications for all interested parties or users of the sustainability report, as it provides increased transparency and accountability over organisational operations, allowing these stakeholders to make more informed decisions such as; purchasing choices (consumers), supply chain relationships (suppliers), prospective employment opportunities (employees) and even allowing organisations to operate in different jurisdictions (government, regulators and communities). The extent of influence these reports have over internal and external stakeholder decision-making are therefore significant, and businesses are increasingly recognising this.[13] We will explore the notion of TBL in detail later in Section 11.4.

So how does this relate to management accounting? Increasingly, corporate and broader society around which organisations exist are beginning to acknowledge the importance of valuing the physical environment within which we exist, in order to better appreciate the true cost of our actions, at both a corporate and individual level. Businesses have started thinking more deeply about how they might use accounting to identify and measure their environmental costs and broadly conceptualise the sustainability of their pursuits. For example, Qantas provides customers with a ‘Fly Carbon Neutral’ option to pay for their share of carbon emissions from flights. Management accounting measures, analyses, and reports financial and non-financial information that helps managers make decisions to fulfil the goals of an organisation.[14] Financial information is disclosed in financial reporting and takes a quantitative form, whereas non-financial information incorporates environmental and social data which can take a qualitative or quantitative form. Cost accounting also has a bearing here as it measures, analyses, and reports financial and non-financial information relating to the costs or acquiring or using resources in an organisation.[15] Hence the true costs of operations can include for example, raw materials (economic), damage to the environment (environmental), adverse impacts to communities (social) and so on.

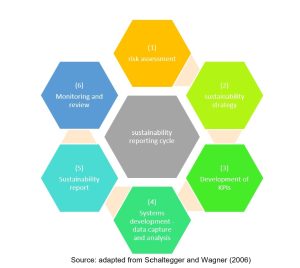

Organisations can absorb benefits from recognising and mitigating negative impacts of environmentally and socially adverse outcomes caused by their operations. For example, in 1991 to 1992 DuPont was helped by the US Environmental Protection Agency to reduce its toxic emissions by 50%, costing around US$3.8 million, however savings were found to be US$15.8 million per year as they avoided environmental compliance costs.[16] Without managerial cooperation and organisational restructuring of systems, processes, practices and performance measurement these improvements would not have been made. Understanding the associated costs of poor sustainability behaviours requires risk assessment, strategy development, followed by the establishment of key performance indicators, systems development including methods to capture and analyse relevant data, culminating in the reporting of sustainability performance.[17] Risk assessment (phase 1) identifies sustainability risk exposures across the organisation. Strategy development (phase 2) requires the organisation to determine their overall approach to sustainability, which often requires a collaborative approach with various stakeholders, both internal and external, thus connecting and committing stakeholders to an organisational direction.[18] Development of Key Performance Indicators (KPI) (phase 3) provides links between the business’s sustainability values/strategies and organisational performance in meeting those values/strategies. As such KPI is defined as a factor(s) by reference to which the development, performance, or position of the business of the company can be measured effectively.[19] Systems development (phase 4) requires organisations to adapt systems, policies, and practices to capturing relevant sustainability data in order to interpret and analyse performance then compare this information to pre-assigned targets. This aids managers in determining organisational effectiveness in achieving sustainability targets and if falling short of the mark, provides opportunities to redefine goals and objectives which are achievable and meaningful.[20] The final part (phase 5) is reporting the information, which is the primary focus of this topic. The monitoring and review phase (6) determines the effectiveness of the cycle including the sustainability report itself and provides opportunities to improve the process.[21] These phases are represented in the sustainability reporting cycle (diagram 1) below:

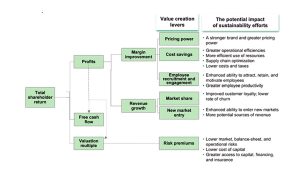

Businesses do not have to sacrifice profit in order to be sustainable, and here management accounting can provide concrete analyses to highlight how in the medium to longer term, using less resources or using them smarter has fundamental economic benefits! Sustainability can plausibly co-exist with profitability (World Economic Forum, 2020) and investments in sustainability practices can in fact even add to shareholder return as illustrated in the flowchart below:

Through pricing power (a sustainable brand has the ability to price its goods and services at a higher price), cost savings (through greater operational efficiencies and more efficient use of resources), easier employee recruitment (employees are increasingly likely to apply for and accept jobs from companies they view as environmentally sustainable – IBM Survey), higher market share (due to increased customer loyalty), access to broader markets (sustainability as a market differentiator) and lower risk premiums (sustainable companies get a lower cost of capital), sustainability investments have the potential to fundamentally change how businesses perform economically.

Through pricing power (a sustainable brand has the ability to price its goods and services at a higher price), cost savings (through greater operational efficiencies and more efficient use of resources), easier employee recruitment (employees are increasingly likely to apply for and accept jobs from companies they view as environmentally sustainable – IBM Survey), higher market share (due to increased customer loyalty), access to broader markets (sustainability as a market differentiator) and lower risk premiums (sustainable companies get a lower cost of capital), sustainability investments have the potential to fundamentally change how businesses perform economically.

Keeping It Real: Deloitte 2022 CxO Sustainability Report – Australia

In a survey of 750 Australian company key executives performed in January to February 2021 by Deloitte Touche Tohmatsu (Deloitte) a majority of Australian executives say their companies (75%) are very concerned about climate change and almost all (95%) contended their companies had been adversely impacted by climate change related events, including disruptions to supply chains.[1] Despite the doom and gloom, there is a feeling of hope as 89% of survey respondents indicated immediate action could mitigate these deleterious outcomes.[2] To combat these escalating issues these surveyed organisations are:

- Developing sustainable goods and services.

- Updating and/relocating organisational facilities to resist climate impacts.

- Incorporating managerial compensation to sustainability performance.

- Requiring supply chain businesses and partners to meet sustainability requirements.

- Taking a considered approach to lobbying and political support through focussed donations to political representatives taking a leadership role in climate change.[3]

These efforts indicate a need for organisations to embed sustainability practices into organisational culture commencing with sound leadership in executive level staff which informs organisational direction for all employees.[4]

[1] Deloitte Touche Tohmatsu. (2022). Deloitte 2022 CxO sustainability report: The disconnect between ambition and impact Australia. https://www2.deloitte.com/au/en/pages/about-deloitte/articles/cxo-sustainability-report.htm

[2] ibid

[3] Deloitte Touche Tohmatsu. (2022). Deloitte 2022 CxO sustainability report: The disconnect between ambition and impact Australia. https://www2.deloitte.com/au/en/pages/about-deloitte/articles/cxo-sustainability-report.htm

[4] Ibid

Value Reporting Foundation. (2021). Transition to integrated reporting: A guide to getting started. https://www.integratedreporting.org/resource/international-ir-framework/. (accessed 25 September 2022).

[1] World Commission on Environment and Development. (1987). Report for the World Commission on Environment and Development: Our common future. https://sustainabledevelopment.un.org/content/documents/5987our-common-future.pdf

[2] World Commission on Environment and Development. (1987). Report for the World Commission on Environment and Development: Our common future. https://sustainabledevelopment.un.org/content/documents/5987our-common-future.pdf p. 16 (accessed 24 September 2022).

[3] Climate Council. (2020). Burning issue: The black summer film all Australians must see. https://www.climatecouncil.org.au/resources/burning-issue-black-summer-film-all-australians-must-see/ (accessed 24 September 2022).

[4] Rice, M., Hughes, L., Bradshaw, S., Bambrick, H., Hutley, N., Arndt, D., Dean, A., & Morgan, W. (2022). A supercharged climate: Rain bombs, flash flooding and destruction. The Climate Council. https://www.climatecouncil.org.au/resources/supercharged-climate-rain-bombs-flash-flooding-destruction/ . (accessed 24 September 2022).

Climate Council. (2022). Pull your weight: Australia’s biggest polluters on notice. https://www.climatecouncil.org.au/resources/australias-biggest-polluters-on-notice/ (accessed 24 September 2022)

[5] PwC. (2022). Sustainability in retail and consumer goods: Added cost or source of value? https://www.pwc.com.au/retail-consumer-markets/sustainability-in-retail-and-consumer-goods.html. (accessed 24 September 2022).

[6] Owens, K. A. and S. Legere (2015). What do we say when we talk about sustainability?: Analyzing faculty, staff and student definitions of sustainability at one American university. International journal of sustainability in higher education 16(3): 367-384.

Urdan, M. S. and P. Luoma (2020). Designing effective sustainability assignments: How and why definitions of sustainability impact assignments and learning outcomes. Journal of management education 44(6): 794-821.

[7] Spitzeck, H. (2013). Elkington, John. In: Idowu, S.O., Capaldi, N., Zu, L., Gupta, A.D. (eds) Encyclopedia of Corporate Social Responsibility. Springer, Berlin, Heidelberg. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-642-28036-8_211 . https://link.springer.com/referenceworkentry/10.1007/978-3-642-28036-8_211#citeas

[8] Elkington, J. (1997). Accounting for the triple bottom line. Measuring Business Excellence 2(3): 18-22.

[9] ibid

[10] ibid

[11] ibid

[12] ibid

[13] PwC. (2022). Sustainability in retail and consumer goods: Added cost or source of value? https://www.pwc.com.au/retail-consumer-markets/sustainability-in-retail-and-consumer-goods.html. (accessed 24 September 2022).

[14] Horngren, C., Datar, S., Rajan, M., Wynder, M., Maguire, W., & Tan, R. (2013). Cost Accounting. (2nd ed.). P.Ed Australia. p. 5.

[15] ibid

[16] Yoo, S., Eom, J., & Han, I. (2020). Too costly to disregard: The cost competitiveness of environmental operating practices. Sustainability (Basel, Switzerland), 12(15), 5971–. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12155971

[17] Schaltegger, S. and M. Wagner (2006). Managing sustainability performance measurement and reporting in an integrated manner: Sustainability accounting as the link between the sustainability balanced scorecard and sustainability reporting. Sustainability Accounting and Reporting. 681-697.

[18] Kantabutra, S. (2020). “Toward an Organizational Theory of Sustainability Vision.” Sustainability 12(3): 1125. https://www.mdpi.com/2071-1050/12/3/1125/htm

[19] Elzahar, H., Hussainey, K., Mazzi, F., & Tsalavoutas, I. (2015). Economic consequences of key performance indicators’ disclosure quality. International Review of Financial Analysis, 39, 96–112. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.irfa.2015.03.005

[20] Schaltegger, S. and M. Wagner (2006). Managing sustainability performance measurement and reporting in an integrated manner: Sustainability accounting as the link between the sustainability balanced scorecard and sustainability reporting. Sustainability Accounting and Reporting. 681-697.

[21] Kaur, A. and S. Lodhia (2018). Stakeholder engagement in sustainability accounting and reporting: A study of Australian local councils. Accounting, auditing, & accountability. 31(1): 338-368.