7.3 Understand the effects of adjustments that may be made during a non-current asset’s useful life

Rina Dhillon

Since non-current assets (hereafter NCA) are used over many years, businesses sometimes account for some events for NCA that are less routine than recording purchase and depreciation. For example, a business may realise that its original estimate of useful life or salvage value is no longer accurate. Or a NCA may lose its value. In such cases, the business must make adjustments as new information is available or as new activity happens. These adjustments may arise from the following three instances:

(1) Changes in estimates (e.g. useful life or residual value)

(2) Additional expenditures which improve the non-current asset’s use and value

(3) Significant declines in the asset’s net realisable value (e.g. manufacturer recall)

Let’s examine each of these instances closely.

(1) Changes in estimates

As you have learned, depreciation is based on estimating both the useful life of an asset and the salvage value of that asset. Over time, these estimates may be proven inaccurate and need to be adjusted based on new information. When this occurs, the depreciation expense calculation should be changed to reflect the new (more accurate) estimates. For this entry, the remaining depreciable balance of the asset’s carrying value is allocated over the new useful life of the asset. To work through this process with data, let’s return to the example of MAAS Corporation.

MAAS Corporation purchased a machine for $100000 on 1st January, with a 10-year useful life and $10000 residual value. Using straight-line, MAAS Corporation records $9000 depreciation expense each year, calculated and recorded as follows:

Depreciation = (100000-10000)/10 = $9000

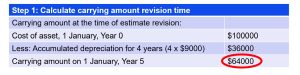

At the start of Year 5, MAAS determines that the estimated useful life of the machine would have been more accurately estimated at eight years, and the salvage value at that time would be $4000. The revised depreciation expense can be calculated using three steps. First, we must calculate the carrying amount of the asset on the date of revision, which represents the unexpired cost of the asset:

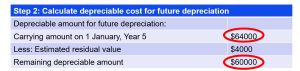

In the second step, we subtract the asset’s residual value (new estimate) from the carrying amount calculated in Step 1 which will result in the asset’s remaining depreciable amount:

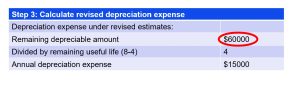

Finally, under the straight line method, we calculate depreciation expense by dividing the remaining depreciable amount, calculated in Step 2, by the remaining useful life. In this example, the useful life is now 8 years instead of 10 years which means there are only 4 (8-4) years remaining instead of 6 years.

These revised calculations show that MAAS should now be recording a depreciation of $15000 per year for the next four years. It is important to note that when an estimate is revised, the change is made prospectively. This means that the change affects only the calculation of current and future depreciation expense, it will not correct prior years (in the example, the first four years). Once the estimate is changed, prospective (current and future) depreciation expense is calculated with the new estimate.

(2) Additional expenditures which improve the non-current asset’s use and value

Most non-current assets require expenditures throughout their useful lives. The purchasing price of a truck is only the initial cost. Expenditures such as servicing, minor/major repairs, etc is part of owning the asset. The accounting treatment for expenditures made during the useful life of a non-current asset depends on whether they are classified as ‘capital’ or ‘revenue’ expenditures. A capital expenditure increases the expected useful life or productivity of the asset (i.e. increases the asset value), while a revenue expenditure maintains the expected useful life or productivity of the asset (i.e. does not enhance the asset and is therefore expensed).

Whether an expenditure made is capitalised (capital expenditures) or expensed in the period in which they are incurred (revenue expenditures) depends on whether the expenditure meets the recognition criteria in AASB 116 Property, Plant and Equipment, paragraph 7:

The cost of an item of property, plant and equipment shall be recognised as an asset if, and only if: (a) it is probable that future economic benefits associated with the item will flow to the entity;

and; (b) the cost of the item can be measured reliably.

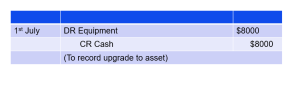

To illustrate, suppose MAAS Corporation purchases equipment for $100000 on 1st July, with a five-year useful life and no residual (salvage) value. During the fifth and final year of the asset’s life, the company incurs $8000 for upgrades that extend the asset’s life for three years, from 5 to 8 years. The $8000 for upgrades meet the recognition criteria in AASB 116 as the asset’s useful life is extended by 3 years and thus should be capitalised with the following entry:

The above entry increases the equipment (asset) account and decreases cash (asset). It does not change equity because the business is capitalising the expenditure rather than expensing it.

With this addition to the cost of the asset, depreciation expense must be recalculated. To do so, the business follows the same steps used in the change of estimate example illustrated above:

First, MAAS corporation calculates the carrying amount of the asset and then adds the capital expenditure to obtain the updated carrying amount which is $28000. Next the business subtracts the asset’s residual value from the updated carrying amount to calculate the remaining depreciable amount. Under the straight line method of depreciation, the depreciable amount is divided by the remaining useful life to obtain depreciation expense – in this case it would $7000 each year.

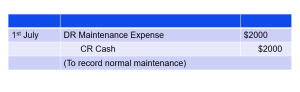

Let us now assume that during the fifth and final year of the equipment’s life, MAAS Corporation incurs $2000 in ordinary maintenance. In this scenario, the $2000 is a revenue expenditure and should be expensed as follows:

The above entry increases maintenance expense (debit) and decreases cash (credit). Repairs and maintenance maintain, rather than increase or enhance, the productivity or useful life of the asset and thus should not be added to the cost of the asset, but expensed in the period in which they are incurred.

Sometime technological improvements or changing market conditions causes a non-current asset’s recoverable amount to fall substantially. When a non-current asset’s recoverable amount (i.e. how much it can be sold for in the market) falls below its carrying amount, the asset is considered impaired. AASB 136 Impairment of Assets, para 18 defines recoverable amount as:

the higher of an asset’s or cash-generating unit’s fair value less costs of disposal and its value in use.

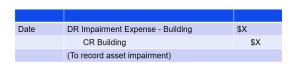

Under AASB 136, businesses apply conservatism by writing these assets down from their carrying amount to their recoverable amount (through use or sale). An impairment is an expense that lowers the value of a non-current asset and thus the following journal entry will be recorded (for example if a building was impaired):

In the above entry, impairment expense is increased to reflect the decline in value of the asset, which reduces equity. This impairment expense is considered to be part of the income statement and would be included in other expenses. In addition, the NCA account (in this example the NCA is a building) decreases to reflect the reduced value. This reduces assets. After the impairment entry, depreciation expense would be calculated based on the revised depreciable amount and over the remaining useful life of the asset.

Asset impairments are not uncommon in practice. AASB 136, paragraph 9 requires entities to ‘assess at the end of each reporting period whether there is any indication that an asset may be impaired. If any such indication exists, the entity shall estimate the recoverable amount of the asset‘.