5.3 Understand the methods used to account for uncollectible receivables (bad debts), estimate bad debt expense and manage the provision for doubtful debts

Rina Dhillon; Mitchell Franklin; Patty Graybeal; and Dixon Cooper

As stated in the previous section, accounts receivable are reported on the balance sheet as an asset. But at what amount? The amount owed by a customer? Not always! Although each customer must satisfy a business’ credit requirements before a credit sale is approved, inevitably some accounts receivable will not be collected – the customer defaults and never pays the account – known as uncollectible receivable or uncollectible accounts.

Uncollectible accounts, which is more commonly known as bad debt expense, is included in the calculation of profits (or losses). An uncollectible account is written-off (the asset is removed) and an expense is recognised. Because uncollectible accounts are a normal part of any business, bad debt expense is considered an operating expense. Bad debt negatively affects accounts receivable. When future collection of receivables cannot be reasonably assumed, recognising this potential nonpayment is required. When the expense is recognised depends on the method of accounting for uncollectible accounts. There are two methods a business may use to recognise bad debt: (1) the direct write-off method and (2) the allowance method. Let’s look at these methods closely.

Direct write-off method

The direct write-off method delays recognition of bad debt until the specific customer accounts receivable is identified. Once this account is identified as uncollectible, the business will record a reduction to the customer’s accounts receivable and an increase to bad debt expense for the exact amount uncollectible.

Under generally accepted accounting principles (GAAP), the direct write-off method is not an acceptable method of recording bad debts, because it violates the matching principle. For example, assume that a credit transaction occurs in September 2021 and is determined to be uncollectible in February 2022. The direct write-off method would record the bad debt expense in 2022, while the matching principle requires that it be associated with a 2021 transaction, which will better reflect the relationship between revenues and the accompanying expenses. This matching issue is the reason accountants will typically use one of the two accrual-based accounting methods introduced to account for bad debt expenses.

It is important to consider other issues in the treatment of bad debts. For example, when a business accounts for bad debt expenses in their financial statements, it will use an accrual-based method; however, they are required to use the direct write-off method on their income tax returns. This variance in treatment addresses taxpayers’ potential to manipulate when a bad debt is recognised. Because of this potential manipulation, the Australian Taxation Office (ATO) requires that the direct write-off method must be used when the debt is determined to be uncollectible, while GAAP still requires that an accrual-based method be used for financial accounting statements.

For the taxpayer, this means that if a business sells an item on credit in October 2021 and determines that it is uncollectible in June 2022, it must show the effects of the bad debt when it files its 2022 tax return. This application probably violates the matching principle, but if the ATO did not have this policy, there would typically be a significant amount of manipulation on company tax returns. For example, if the business wanted the deduction for the write-off in 2021, it might claim that it was actually uncollectible in 2021, instead of in 2022. This method also does not provide the best estimate of how accounts receivable affect expected cash inflow for the business.

The final point relates to businesses with very little exposure to the possibility of bad debts, typically, entities that rarely offer credit to its customers. Assuming that credit is not a significant component of its sales, these sellers can also use the direct write-off method. The companies that qualify for this exemption, however, are typically small and not major participants in the credit market. Thus, virtually all of the remaining bad debt expense material discussed here will be based on an allowance method that uses accrual accounting, the matching principle, and the revenue recognition rules under GAAP.

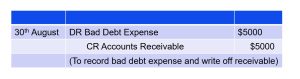

For example, assume Kenco makes a $5000 credit sale to Bennards on 28th March. On 30th August, Kenco Ltd determines that it will be unable to collect from Bennards. When the account defaults for non-payment on 30th August, Kenco would record the following journal entry to recognise bad debt.

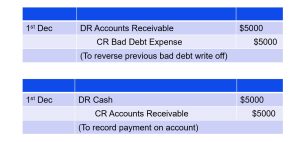

Bad Debt Expense increases (debit), and Accounts Receivable decreases (credit) for $5000. If, in the future, any part of the debt is recovered, a reversal of the previously written-off bad debt, and the collection recognition is required. Let’s say this customer unexpectedly pays in full on 1st December, the business would record the following journal entries:

Bad Debt Expense increases (debit), and Accounts Receivable decreases (credit) for $5000. If, in the future, any part of the debt is recovered, a reversal of the previously written-off bad debt, and the collection recognition is required. Let’s say this customer unexpectedly pays in full on 1st December, the business would record the following journal entries:

The first entry reverses the bad debt write-off by increasing Accounts Receivable (debit) and decreasing Bad Debt Expense (credit) for the amount recovered. The second entry records the payment in full with Cash increasing (debit) and Accounts Receivable decreasing (credit) for the amount received of $5000.

The first entry reverses the bad debt write-off by increasing Accounts Receivable (debit) and decreasing Bad Debt Expense (credit) for the amount recovered. The second entry records the payment in full with Cash increasing (debit) and Accounts Receivable decreasing (credit) for the amount received of $5000.

As you’ve learned above, the delayed recognition of bad debt violates GAAP, specifically the matching principle. Therefore, the direct write-off method is not used for publicly listed companies; the allowance method is used instead.

Allowance method

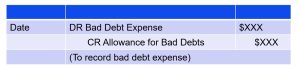

The allowance method is the more widely used method because it satisfies the matching principle. The allowance method estimates bad debt during a period, based on certain computational approaches. The calculation matches bad debt with related sales during the period. The estimation is made from past experience and industry standards. Essentially, the allowance method splits the accounting into two entries, firstly an entry to record an estimate of bad debt expense and secondly an entry to write off receivables when they become uncollectible. When the estimation is recorded at the end of a period, the following entry occurs:

The journal entry for the Bad Debt Expense increases (debit) the expense balance, and the Allowance for Doubtful Accounts increases (credit) the balance in the Allowance. When setting up the allowance, the allowance account is a contra asset account, and is subtracted from Accounts Receivable to determine the Net Realisable Value of the Accounts Receivable account on the balance sheet. This means that when it is subtracted from Accounts Receivable, the difference represents an estimate of the cash value of accounts receivable. The contra account may also be called the Provision for Bad Debts or the Allowance for Bad Debts in practice.

A contra account has an opposite normal balance to its paired account, thus reducing or increasing the balance in the paired account at the end of a period; the adjustment can be an addition or a subtraction from a controlling account. In the case of the Allowance for bad debts, it is a contra account that is used to reduce the Controlling account, Accounts Receivable. At the end of an accounting period, the Allowance for bad debts reduces the Accounts Receivable to produce Net Accounts Receivable. Note that allowance for bad debts reduces the overall accounts receivable account, not a specific accounts receivable assigned to a customer. Because it is an estimation, it means the exact account that is (or will become) uncollectible is not yet known.

To calculate the most accurate estimation possible, a company may use one of three approaches for bad debt expense recognition: the percentage of credit sales approach, the percentage of receivables approach, or aging of receivables approach. Let’s examine each of these approaches in detail.

Percentage-of-credit sales approach

The percentage of credit sales approach (also known as the income statement approach) estimates bad debt expenses based on the assumption that at the end of the period, a certain percentage of sales during the period will not be collected. The estimation is typically based on credit sales only, not total sales (which include cash sales). In this example, assume that any credit card sales that are uncollectible are the responsibility of the credit card company. It may be obvious intuitively, but, by definition, a cash sale cannot become a bad debt, assuming that the cash payment did not entail counterfeit currency.

The percentage of credit sales approach is a simple way to calculate bad debt, but it may be more imprecise than other measures because it does not consider how long a debt has been outstanding and the role that plays in debt recovery. In addition, under the percentage of credit sales approach, we ignore any existing balance in the allowance when calculating the amount of the year-end adjustment.

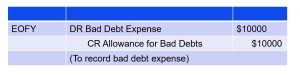

To illustrate, let’s continue to use Kenco Ltd as the example. Suppose Kenco Ltd has made $500000 of sales and estimates that it will not collect 2 per cent of those sales. The following adjusting journal entry at the end of the financial year for bad debt would be:

Bad Debt Expense increases (debit), and Allowance for bad debts increases (credit) for $10000 ($500000 × 2%). This means that Kenco believes $10000 will be uncollectible debt. As mentioned above, a second entry to write off receivables is made when they become uncollectible. To illustrate a receivables write off, assume that the credit manager of Kenco Ltd authorises a write off of the $5000 balance owed by Bennards on 1st August. The entry to record the write off is:

Bad Debt Expense increases (debit), and Allowance for bad debts increases (credit) for $10000 ($500000 × 2%). This means that Kenco believes $10000 will be uncollectible debt. As mentioned above, a second entry to write off receivables is made when they become uncollectible. To illustrate a receivables write off, assume that the credit manager of Kenco Ltd authorises a write off of the $5000 balance owed by Bennards on 1st August. The entry to record the write off is:

Bad debt expense is not increased when a write off occurs. Under the Allowance method, every bad debt write off is debited to the Allowance for Bad Debts account as a debit to Bad Debt Expense would be incorrect given that the expense has already been recognised when the adjusting entry was made for the estimated bad debts. Instead, the entry to record the write off of an uncollectible account reduces both Accounts Receivables and the Allowance for Bad Debts.

Percentage-of-receivables approach

The percentage of receivables approach (also known as the balance sheet approach) estimates bad debt expenses based on the balance in accounts receivable. This approach looks at the balance of accounts receivable at the end of the period and assumes that a certain amount will not be collected. Accounts receivable is reported on the balance sheet; thus, it is also known as the balance sheet approach.

This approach is less straightforward and requires working out what the closing balance should be and then depending on the current balance, the adjustment is the bad debt expense. This approach is calculated in two steps:

(1) Calculate what the balance in the Allowance for Bad Debts account should be by multiplying accounts receivables by a percentage set by the business;

(2) Adjust the Allowance for Bad Debts account to the balance calculated in step (1).

Thus it is important to note that the percentage of receivables approach considers any existing balance in the allowance when calculating the amount of bad debt expense. To illustrate, let’s assume that Kenco has a receivables balance of $25000 at the end of the financial year. Based on past experience, the business expects that 1% of its receivables balance will be uncollectible.

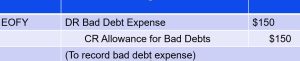

As a result, the balance in the allowance account at year end should be 1% of receivables, or a $250 credit balance ($25000 X 1%) which provides us with the final calculation for Step 1. Suppose the Allowance for Bad Debts account already has an existing balance of $100 credit. To get the balance to a $250 credit requires a $150 credit entry and thus the adjustment required to reflect the bad debt expense is $150 ($250-100). This is illustrated as follows:

Bad Debt Expense increases (debit), and Allowance for Doubtful Accounts increases (credit) for $150. This journal entry takes into account a credit balance of $100 and subtracts the prior period’s balance from the estimated balance in the current period of $250.

The percentage of receivables approach is another simple approach for calculating bad debt, but it too does not consider how long a debt has been outstanding and the role that plays in debt recovery. However, there is a variation on the balance sheet approach, called the aging of receivables approach that does consider how long accounts receivable have been owed, and it assigns a greater potential for default to those debts that have been owed for the longest period of time. We turn our attention to this approach now.

Aging of Receivables Approach

Many businesses use a more refined version of the percentage-of-receivables approach, known as the Aging of receivables approach. This approach estimates bad debt expenses based on the balance in accounts receivable, but it also considers the uncollectible time period for each account. The longer the time passes with a receivable unpaid, the lower the probability that it will get collected. An account that is 90 days overdue is more likely to be unpaid than an account that is 30 days past due.

With this approach, accounts receivable is organised into categories by length of time outstanding, and an uncollectible percentage is assigned to each category. The length of uncollectible time increases the percentage assigned. For example, a category might consist of accounts receivable that is 1–30 days past due and is assigned an uncollectible percentage of 3%. Another category might be 31–60 days past due and is assigned an uncollectible percentage of 15%. All categories of estimated uncollectible amounts are summed to get a total estimated uncollectible balance. That total is reported in Bad Debt Expense and Allowance for Doubtful Accounts, if there is no carryover balance from a prior period. If there is a carryover balance, that must be considered before recording Bad Debt Expense.

The aging of receivables approach is more complicated than the other two approaches, but it tends to produce more accurate results. This is because it considers the amount of time that accounts receivable has been owed, and it assumes that the longer the time owed, the greater the possibility that individual accounts receivable will prove to be uncollectible. Looking at Kenco Ltd, it has an accounts receivable balance of $25000 at the end of the year. Kenco splits its past-due accounts into four categories: 1–30 days past due, 31–60 days past due, 61-90 days past due and over 90 days past due. The uncollectible percentages and the accounts receivable breakdown are shown in the table below:

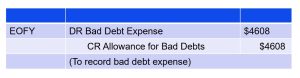

For each of the individual categories, we would multiply the uncollectible percentage by the accounts receivable total for that category to get the total balance of estimated accounts that will prove to be uncollectible for that category. Then all of the category estimates are added together to get one total estimated uncollectible balance for the period. The entry for bad debt would be as follows, if there was no carryover balance from the prior period.

Bad Debt Expense increases (debit) as does Allowance for Doubtful Accounts (credit) for $4608. Kenco believes that $4608 will be uncollectible debt.

Let’s consider a situation where Kenco had a $2000 debit balance from the previous period. The adjusting journal entry would recognise the following:

This journal entry takes into account a debit balance of $2000 and adds the prior period’s balance to the estimated balance of $4608 in the current period, providing for a bad debt of $6608 ($4608+2000).

This journal entry takes into account a debit balance of $2000 and adds the prior period’s balance to the estimated balance of $4608 in the current period, providing for a bad debt of $6608 ($4608+2000).

You may notice that all three approaches use the same accounts for the adjusting entry; only the approach changes the financial outcome. Also note that it is a requirement that the estimation approach be disclosed in the notes of financial statements so stakeholders can make informed decisions.

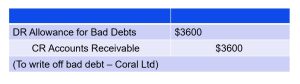

Writing off specific accounts using the allowance method

When a business decides that a particular customer account is uncollectible, that account is removed by debiting the allowance for bad debts and crediting accounts receivable for that specific customer. This process is called ‘writing off the bad debt’ or ‘writing off the account’. Let’s assume Kenco determines at the end of the financial year that a $3600 receivable from Coral Ltd is uncollectible and decides to write it off. The journal entry will be as follows:

This entry has no effect on Kenco’s carrying amount of receivables. This is because both the asset account and the contra-asset account are decreasing by the same amount, thereby offsetting one another.

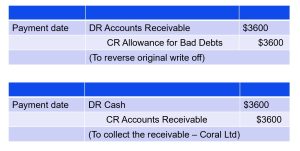

Recovery of a write-off

At times, a business will collect a receivable previously written off. When this payment occurs, two entries are made: (1) the first entry reverses the original write off and (2) the second entry records the collection of cash and the reduction of the receivable. Suppose Coral Ltd pays their bill in full. When the payment is made, the following two entries are created:

Notice that once again that there is no effect on total assets by either of the above two entries.