4.4 Describe various business transactions that can happen in a partnership

Rina Dhillon; Mitchell Franklin; Patty Graybeal; and Dixon Cooper

Commencement of a Partnership

One of the characteristics of a partnership is multiple owners (some Big 4 Accounting Firms in Australia have hundreds of partners – some of which are equity partners while others salaried partners). Unlike shareholders in a company who contribute cash and are not involved in the day to day running of the business beyond attending and voting at the annual general meetings, partners contribute assets and liabilities and thus are entitled to participate in the management of the business (although in larger professional partnerships like the Big 4 Accounting Firms, this management functions might be delegated to a senior management team).

Partnerships are often the result of combining two existing businesses (like Ben and Jerry) with assets such as cash, accounts receivables, property, plant and equipment and liabilities such as accounts payable and bank loans. Each partner will contribute assets and liabilities as initial contribution to the business and each partner’s initial contribution is recorded on the partnership’s books at the fair value of the net asset at the date of transfer. The value of these initial contributions before the partnership is irrelevant – what is important is the value of these contributions to the partnership. The new partnership is buying the assets and assuming the responsibility of liabilities and thus we value each contribution at the current (and agreed) value.

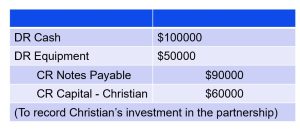

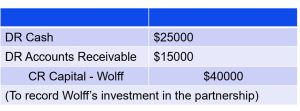

As an example, let’s go back to Christian and Wolff. On January 1, they combined their resources into a general partnership named Christian and Wolff – Accountants. They agree that Christian contributes cash of $100000, equipment that has a cost of $30000, accumulated depreciation of $3000, and current market value of $50000 (the current price at which it would sell), and a note payable $90000. Wolff contributes cash of $25000 and accounts receivables of $15000.

Note this point about the commencement of a partnership when its assets’ fair market value differs from their book value: it wouldn’t make sense to base the value of the capital contribution of assets (or liabilities) on their book value. To see why, consider the equipment contribution made by Christian. The equipment had a book value of $27000 (Cost of $30000 less accumulated depreciation of $3000) and a fair value of $50000. Why should Dale get credit for a contribution of only the $27000 book value when he could have sold the equipment for $50000 and contributed $50000 in cash, instead for the equipment with a fair value of $50000?

Likewise, if the partnership were to assume liabilities from one of the partners, the liability would be recorded at the current value. And, as demonstrated above, any non-cash assets contributed to the partnership should be valued at their current values. In addition, when used fixed assets are contributed, depreciation is calculated based on their fair value and the partnership’s estimate of their useful life. Fixed assets are contributed at their fair value, not the book value on the partner’s individual books before the commencement of the partnership.

Given that in a partnership, each partner may contribute different assets (and liabilities), receive different amounts of profit or loss, and withdraw different amounts at different times, these transactions are tracked by giving each partner their own partnership capital account. The capital account of each partner records the fair value of net asset contributed. Following from the contributions of Christian and Wolff above, we would record the following journal entries for Christian and Wolff’s contribution

It is important to note that the equipment was entered at the current market value – no accumulated depreciation was recorded because the partnership was buying the asset from Christian, and with the purchase of any asset, the previous owner’s accumulated depreciation is irrelevant.

Allocation of profits and losses

At the end of each financial year, partners would meet to review the income and expenses. Once that has been done, they need to allocate the profit or loss based upon their agreement. If there is no partnership agreement or the agreement does not explicitly stipulate the sharing of profits and losses, then it would be shared equally.

Not every partnership allocates profit and losses on a 50:50 basis. In a partnership, each partner usually contributes different resources and skills and would like to be rewarded for each of them. These may include:

That is why it is very important for the partnership agreement to delineate how the partners will share net income and net losses. The partnership needs to find a methodology that is fair and will equitably reflect each partner’s service and financial commitment to the partnership. The following are examples of typical ways to allocate income:

- A fixed ratio where income is allocated in the same way every period. The ratio can be expressed as a set percentage (for example 80% and 20%), a proportion (7:3) or a fraction (1/4, 3/4).

- A ratio based on beginning-of-year capital balances, end-of-year capital balances, or an average capital balance during the year.

- Partners may receive a guaranteed salary, and the remaining profit or loss is allocated on a fixed ratio.

- Income can be allocated based on the proportion of interest in the capital account. If one partner has a capital account that equates to 75% of capital, that partner would take 75% of the income.

- Some combination of all or some of the above methods.

A fixed ratio is the easiest approach because it is the most straightforward. As an example, assume that Christian and Wolff contributed the same amount of capital. However, Christian works full time for the partnership and Wolff works part time. As a result, the partners agree to a fixed ratio of 0.75:0.25 to share the net income.

Selecting a ratio based on capital balances may be the most logical basis when the capital investment is the most important factor to a partnership. These types of ratios are also appropriate when the partners hire a management team to run the partnership in their place and do not take an active role in daily operations. The last three approaches on the list recognise differences among partners based upon factors such as time spent on the business or capital invested in it.

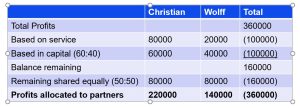

Let’s return to the partnership with Christian and Wolff to see how profits would be allocated. Let’s assume that Christian and Wolff make $360000 profit in their first year. The partnership agreements states the following allocation rules:

The first $100000 is based on service. Christian performs 80% of the total service. The next $100000 is shared based on capital contributed. Remaining profits (or losses) are shared equally.

Allocating the $360000 profit to Christian and Wolff becomes a mathematical exercise in following what was stipulated in the partnership agreement and allocating the profits accordingly:

As the first $100000 is allocated based on service and Christian provides 80% of the service (thus Wolff provides 100-80 = 20%), Christian will receive $80000 and Wolff $20000. The next $100000 is shared based on initial capital contributed. On commencement of the partnership above, Christian contributed $60000 and Wolff contributed $40000. The total initial contribution is $60000+40000 = $100000, thus Christian contributed 60% (60000/100000) and Wolf 40% (40000/100000) giving a 60:40 ratio of allocating the next $100000. Therefore, Christian will receive $60000 and Wolff $40000. Lastly the remaining profits are shared equally. What remains after allocating the $200000 is $160000 ($360000-200000) which will be allocated 50:50, thus both Christian and Wolff will receive $80000 ($160000 x 50%). After this mathematical exercise, Christian will be allocated a total of $220000 ($80000+60000+80000) of the $360000 profit and Wolff will be allocated a total of $140000 ($20000+40000+80000).

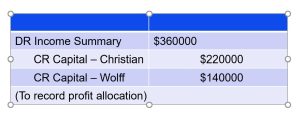

The journal entry would be as follows:

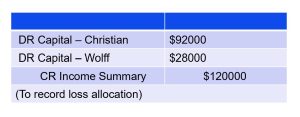

Now, consider the same scenario for Christian and Wolff – Accountants, but instead of a profit, they realise a loss of $120000. The distribution process for allocating a loss is the same as the allocation process for distributing a profit, as demonstrated above. The calculation for the sharing of the loss between the partners is shown below:

Now, consider the same scenario for Christian and Wolff – Accountants, but instead of a profit, they realise a loss of $120000. The distribution process for allocating a loss is the same as the allocation process for distributing a profit, as demonstrated above. The calculation for the sharing of the loss between the partners is shown below:

As we have already seen in the previous section, the balance sheet shows a capital account for each partner. In the income statement, the allocation of profits is shown at the bottom. The statement of change in equity is the most informative statement of each partner’s relationship to the partnership. This statement begins with the opening balance of each partner’s capital. Any additional capital and profits allocated are added and drawings are deducted to obtain the closing balance. Complexity arises when partners join or leave, assets are revalued, or the partnership dissolves but these matters are beyond the scope of this textbook and 22208 Accounting, Business and Society.

We now turn our attention to the various business transactions that can happen in a company.