3.2 Four major circumstances in which adjusting journal entries are necessary

Rina Dhillon; Mitchell Franklin; Patty Graybeal; and Dixon Cooper

As mentioned in the previous section, while adjusting entries can vary significantly across businesses, these entries come about because the earning of revenue or incurrence of expenses does not always occur concurrently with the exchange of cash. For example:

Scenario 1: The business may receive the cash before revenue is earned (i.e. before the goods are provided or the services performed) – also known as unearned revenue

Scenario 2: The business may receive the cash after revenue is earned – also known as accrued revenue

Scenario 3: The business may pay cash before an expense is incurred (i.e. goods are used or services consumed) – also known as prepaid expenses

Scenario 4: The business may pay cash after an expense is incurred – also known as accrued expenses

This timing issues between when cash is received/paid and when revenue/expenses are earned/incurred make adjusting entries necessary. Let’s examine why the need for adjusting entries arises before we discuss the four scenarios listed above in further detail.

The Need for Adjusting Entries

Adjusting entries update accounting records at the end of a period for any transactions that have not yet been recorded. These entries are necessary to ensure the income statement and balance sheet present the correct, up-to-date numbers. Adjusting entries are also necessary because the initial trial balance may not contain complete and current data due to several factors:

- The inefficiency of recording every single day-to-day event: some events are not journalised daily because it would not be useful or efficient to do so. Examples are the use of supplies and the earnings of salary and wages by employees

- Some costs are not recorded during the period but must be recognised at the end of the period: Costs such as depreciation, insurance and rent are not journalised during the accounting period because the economic benefit is consumed / expire over time rather than as a result of recurring daily business transactions.

- Some items are forthcoming for which original source documents have not yet been received, for example an electricity bill (most billing cycle is between one and three months) that will not be received until the next accounting period.

There are a few accounting guidelines that also support the need for adjusting entries:

- Revenue recognition principle: Adjusting entries are necessary because the revenue recognition principle requires revenue recognition when earned, thus the need for an update to unearned revenues (Scenario 1).

- Expense recognition (matching) principle: This requires matching expenses incurred to generate the revenues earned, which affects prepayment accounts such as insurance expense and supplies expense (Scenario 3).

- Time period assumption: This requires useful information be presented in shorter time periods such as quarters or months. This means a business must recognise revenues and expenses in the proper period, requiring adjustment to certain accounts to meet these criteria.

The required adjusting entries depend on what types of transactions the business has, but as briefly introduced above, there are four major circumstances/scenarios in which adjusting journal entries are necessary. Adjusting entries requires updates to specific account types at the end of the period. Not all accounts require updates, only those not naturally triggered by an original source document such as a sales invoice or a payment bill. Before we look at recording and posting these four common types of adjusting entries, we discuss each scenario further below.

Scenario 1: Unearned revenues

Recall that unearned revenue (sometimes known as deferred revenue or revenue received in advance) represents a customer’s advanced payment for a product or service that has yet to be provided by the business. Since the business has not yet provided the product or service, it cannot recognise the customer’s payment as revenue but instead must record a liability. Recording the revenue must be deferred until the revenue is earned (i.e goods are provided or services performed). At the end of a period, the business will review the account to see if any of the unearned revenue has been earned. If so, this amount will be recorded as revenue in the current period.

For example, let’s look at a simple example using Netflix. Netflix offers TV series, documentaries and feature films across various genres and languages. The company provides members the ability to receive streaming content through a host of internet-connected devices, including TVs, digital video players, television set-top boxes, and mobile devices. It has approximately 222 million paid subscription members in 190 countries. When Netflix sells an annual (12 months) basic subscription to its monthly video-streaming service to a customer on 1st July, receiving $120, it will debit cash and credit unearned revenue for $120:

In this case, Unearned revenue, which is a liability, increases (credit) and Cash, which is an asset, increases (debit) for $120.

Suppose, Netflix prepares financial statements at the end of each month. As of 31 July, Netflix has provided one month of streaming service and has therefore earned one month of revenue. At the end of the month, after analyzing the unearned revenue account, 1/12 or $10 of the unearned revenue has been earned and as the accounting system does not yet reflect this earned revenue, the following adjusting entry would be made on 31 July to recognise and record the $10 ($120 × 1/12) of revenue:

The entry would then be posted to the relevant T-accounts as follows:

After posting, the revenue T-account reflects the $10 earned in the current accounting period while the unearned revenue T-account reflects the remaining $110 liability still owing and to be earned over the next 11 months. These two accounts have been adjusted to reflect revenues earned during July (which will be depicted in the income statement) and liabilities owed on 31 July (which will be shown in the balance sheet). The cash account is not affected by the adjusting entry – it was recorded on 1 July, the date cash was exchanged.

After posting, the revenue T-account reflects the $10 earned in the current accounting period while the unearned revenue T-account reflects the remaining $110 liability still owing and to be earned over the next 11 months. These two accounts have been adjusted to reflect revenues earned during July (which will be depicted in the income statement) and liabilities owed on 31 July (which will be shown in the balance sheet). The cash account is not affected by the adjusting entry – it was recorded on 1 July, the date cash was exchanged.

Keeping It Real

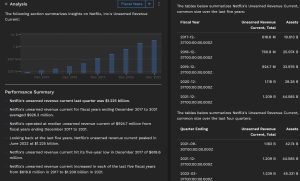

The above Netflix example only provides a glimpse of how unearned revenues would be recorded for a single customer with a basic subscription. In reality, Netflix reported unearned revenue totalling $1.225 B for the latest quarter ending June 30, 2022 on its balance sheet:

Source: Finbox (https://finbox.com/NASDAQGS:NFLX/explorer/unearn_rev_current), assessed 7th July 2022

Source: Finbox (https://finbox.com/NASDAQGS:NFLX/explorer/unearn_rev_current), assessed 7th July 2022

Imagine if Netflix recorded the amounts received as revenue instead of a liability, revenues would be grossly overstated and liabilities understated! As a general rule, when a business receives cash before it provides the goods/services, the business should always increase a liability account for the amount received. As the business provides the service/goods, the liability account is reduced (adjusted down) and the corresponding revenue account is increased (adjusted up).

Scenario 2: Accrued revenues

Accrued revenues are revenues earned in an accounting period but have yet to be recorded, and no money has been collected. Accrued revenues may accumulate (accrue) over time, some examples include interest, and services completed but a bill has yet to be sent to the customer at the end of the accounting period. Interest revenues does not involve daily transactions (accumulating during the period and needs to be adjusted to reflect interest earned at the end of the period) and thus would be unrecorded at the end of the period and revenue related to services / fees may be unrecorded because only a portion of the total service has been provided and the clients will not be invoiced until the service has been completed.

An adjusting entry is required to show the receivable that exists at the end of the accounting period and to recognise and record the revenue for the period. Since there was no bill to trigger a transaction, an adjustment is required to recognise revenue earned at the end of the period. Accordingly, an adjusting entry for accrued revenues results in an increase (a debit) to an asset account and an increase (a credit) to a revenue account.

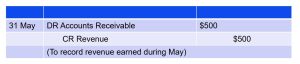

For example, assume a legal firm provides services to a client to appeal a parking fine for $500, completing its work on 23 May. They bill the client on 10 June and receive payment on 21 June. The legal firm closes its books on 31 May. Note that this service has not been paid at the end of the period, only earned. This aligns with the revenue recognition principle to recognise revenue when earned, even if cash has yet to be collected. At the end of the month, the following adjusting journal entry occurs:

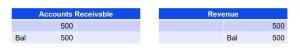

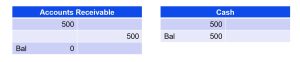

The entry increases the Accounts Receivable (asset) account for the amount that the client owes the legal firm and increases the Revenue (equity) account for the same amount that the firm has earned but had been previously unrecorded. This entry would be posted to the relevant T-accounts as follows:

The entry increases the Accounts Receivable (asset) account for the amount that the client owes the legal firm and increases the Revenue (equity) account for the same amount that the firm has earned but had been previously unrecorded. This entry would be posted to the relevant T-accounts as follows:

After posting, the Revenue T-account illustrates the $500 earned in the current accounting period and the Accounts Receivable T-account shows the $500 of expected cash receipts from the client. These two accounts have been adjusted to accurately reflect revenues earned during May (which will be shown in the income statement) and receivables held on 31 May (which will be depicted in the balance sheet).

After posting, the Revenue T-account illustrates the $500 earned in the current accounting period and the Accounts Receivable T-account shows the $500 of expected cash receipts from the client. These two accounts have been adjusted to accurately reflect revenues earned during May (which will be shown in the income statement) and receivables held on 31 May (which will be depicted in the balance sheet).

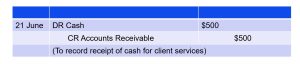

When the client eventually pays the cash on 21st June, the following entry is made in the accounting system:

This entry will increase the Cash account and decrease the Accounts Receivable account for the amount collected. It is important to note that although individual asset accounts are changing, there is no change to total assets. No revenue is also recorded on 21 June as it was already recorded in the prior accounting period when it was earned. This entry would be posted to the relevant T-accounts as follows:

This entry will increase the Cash account and decrease the Accounts Receivable account for the amount collected. It is important to note that although individual asset accounts are changing, there is no change to total assets. No revenue is also recorded on 21 June as it was already recorded in the prior accounting period when it was earned. This entry would be posted to the relevant T-accounts as follows:

Now that we have examined the two common revenue-related adjusting entries, let’s move on to the two scenarios that are related to expenses.

Scenario 3: Prepaid Expenses

Businesses often pay cash for goods/services before it uses or consumes it (i.e. incur an expense), also known as prepaid (sometimes known as deferred) expenses or prepayments. The term prepaid is used because the business has yet to use or consume the goods/services it purchases and thus cannot recognise and record an expense in the accounting system. In other words, the recording of the expense must be deferred until the expense is incurred. It is important to note and understand that prepaid expenses are payments of amounts that will provide future benefits for more than the current accounting period. Given the future benefits over time, when such a cost/expense is incurred, an asset account is increased (debited) to show the benefit or service that would be received in the future.

As soon as the asset has provided benefit to the company, the value of the asset used is transferred from the balance sheet to the income statement as an expense. Some common examples of prepaid expenses are insurance, supplies, depreciation, and rent. Essentially prepaid expenses expire as the services is provided to the business over time (for example insurance and rent) or through use (for example supplies). The expiration of these benefits does not require daily journal entries – it would be very impractical to record every time someone uses supplies (for example a pencil or piece of paper) during the period, so at the end of the period, adjusting entries are made to recognise and record the expenses (value of what has been used) applicable to the current accounting period and the remaining values in the asset accounts. Let’s look at an example of how this is applies to insurance.

Insurance policies can require advanced payment of premiums for several months at a time, twelve month, for example. The business does not use all twelve months of insurance immediately but over the course of the year. At the end of each month, the company needs to record the amount of insurance expired during that month.

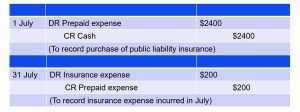

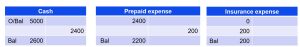

For example, a business purchased a 12-month public liability insurance policy for $2400 on 1 July. It is the end of the first month and the company needs to record an adjusting entry to recognise the insurance used during the month. The following entries show the initial payment for the policy and the subsequent adjusting entry for one month of insurance usage:

In the first entry, Cash decreases (credit) and Prepaid expenses (which is an asset account) increases (debit) for $2400. In the second entry, Prepaid expense decreases (credit) and Insurance Expense increases (debit) for one month’s insurance usage found by taking the total $2400 and dividing by twelve months (2400/12 = 200). The entry would be posted to the relevant T-accounts as follows, and for illustration purposes, assume that the cash account has an opening balance of $5000 prior to entry:

In the first entry, Cash decreases (credit) and Prepaid expenses (which is an asset account) increases (debit) for $2400. In the second entry, Prepaid expense decreases (credit) and Insurance Expense increases (debit) for one month’s insurance usage found by taking the total $2400 and dividing by twelve months (2400/12 = 200). The entry would be posted to the relevant T-accounts as follows, and for illustration purposes, assume that the cash account has an opening balance of $5000 prior to entry:

After posting, the Insurance expense T-account depicts the $200 of insurance that was consumed in the current accounting period (month of July) while the Prepaid expense T-account reflects the remaining $2200 of insurance to be consumed over the next 11 months. These two accounts have been adjusted so that they reflect expenses incurred during July (which will be depicted in the income statement) and unexpired assets on 31 July (which will be shown in the balance sheet). The cash account is not affected by the adjusting entry – it was recorded on 1 July, the date cash was paid for the insurance policy.

Scenario 4: Accrued Expenses

Accrued expenses are expenses incurred in a period but have yet to be recorded, and no money has been paid. Some examples include interest, tax, and salary expenses. Accrued expenses result from the same factors as accrued revenues – in reality, an accrued expense in the records of one business is likely to be accrued revenue to another business. For example, the $500 accrual of service revenue by the law firm in Scenario 2 is an accrued expense to the client who received the legal service.

Accrued expenses adjusting entries are necessary to record the obligations that exist (liabilities) at the end of the reporting period and to recognise the expenses that apply to the current accounting period. In general, an adjusting entry for accrued expenses results in an increase (a debit) to an expense account and an increase (a credit) to a liability account.

For example, many utility companies bill their customers once a month or every three months and the bills usually relate to utility consumption for the prior’s month / quarter. Thus an adjusting entry is needed during the month to show utility expenses incurred but unrecorded and unpaid at the end of the month.

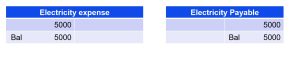

Let’s say Barangaroo Construction consumes $5000 of electricity in July. They receive the electricity bill on 31 July with payment required on 28 August. Barangaroo construction closes its books on 31 July. Because the accrual basis requires that expenses be recorded in the period in which they are incurred, Barangaroo must record the $5000 of expense on 31 July with the following adjusting journal entry:

The preceding journal entry increases the Electricity expense account for the $5000 of electricity incurred during the month of July and increases the Electricity Payable account for the same since it is owing its utility provider $5000. Thus, equity is decreasing and liabilities are increasing, with the following updated ledger balances after posting the adjusting entry:

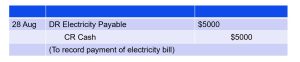

When Barangaroo eventually pays the electricity bill on 28th August, the following entry is made in the accounting system:

When Barangaroo eventually pays the electricity bill on 28th August, the following entry is made in the accounting system:

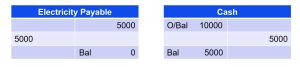

The entry decreases the Cash account for the $5000 paid to the utility provider and decreases the liability (Electricity Payable) account by the same amount. No expenses is recorded as it was already recorded in the prior period when the expense was incurred. Thus both liabilities and assets are decreasing, with the following T-accounts, assuming an opening cash balance of $10000 prior to entry:

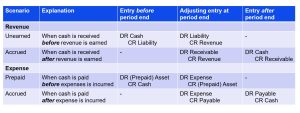

Summary of adjusting journal entries

Important information on each of the four major types of adjusting entries are summarised in the table below. Take some time to study and analyse the adjusting entries. Note that each adjusting entry affects one revenue/expense (income) account and one balance sheet account.

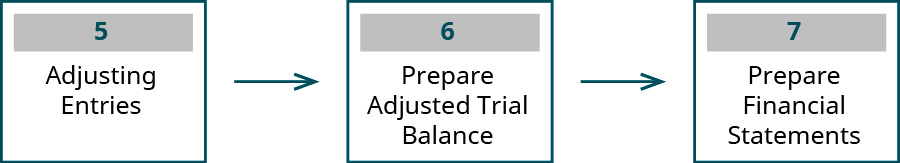

In the next section, we explore these four major adjustments specifically to Kids Learn Online (KLO) – introduced in Chapter 2 – and show how these entries affect Steps 5, 6 and 7 in the accounting cycle: record adjusting entries (journalising and posting), prepare an adjusted trial balance, and prepare the financial statements respectively (attribution: Copyright Rice University, OpenStax, under CC BY-NC-SA 4.0 license).

As we progress through these steps, we will explore why the trial balance in this phase of the accounting cycle is referred to as an “adjusted” trial balance.