2.3 Purpose of the journal, ledger and trial balance

Rina Dhillon; Mitchell Franklin; Patty Graybeal; and Dixon Cooper

When we introduced debits and credits in the last section, you learned about the usefulness of T-accounts as a graphic representation of any account in the general ledger. But before transactions are posted to the T-accounts, they are first recorded as journals (Step 2 of the Accounting Cycle).

Journals

A journal is a chronological record of transactions. Entries recorded in a journal are called journal entries. We use journals to keep track of business transactions. A journal is the first place information is entered into the accounting system and is often referred to as the book of original entry because it is the place the information originally enters into the system. A journal keeps a historical account of all recordable transactions with which the business has engaged. In other words, a journal is similar to a diary for a business. When you enter information into a journal, we say you are journalising the entry. A journal entry (also known as a general journal) include the following information about a transaction:

- the date of the transaction

- the accounts to be debited and credited

- the amounts of the debit and credit entries

- a brief explanation of each transaction

Formatting When Recording Journal Entries

- Include a date of when the transaction occurred.

- The debit account always come first and on the left.

- The credit account always come after all debit accounts are entered, and on the right.

- The credit accounts will be indented below the debit accounts.

- You will have at least one debit (possibly more).

- You will always have at least one credit (possibly more).

- The dollar value of the debits must equal the dollar value of the credits or else the accounting equation will go out of balance.

- You will write a short description after each journal entry.

- Skip a space after the description before starting the next journal entry.

We will show an example of transactions and how they are recorded in a general journal in an example later in the chapter.

Keeping it real: QE Food Stores

QE Food Stores is a chain of grocery stores in Sydney that carries a variety of staple items such as meat, milk, eggs, bread, and so on. As a smaller grocery store, QE Food Stores do not offer the variety of products found in a larger supermarket chains such as Woolworths and Coles. However, it records journal entries in a similar way.

Grocery stores of all sizes must purchase product and track inventory. While the number of entries might differ, the recording process does not. For example, QE Food Stores might purchase food items in one large quantity at the beginning of each month, payable by the end of the month. Therefore, it might only have a few accounts payable and inventory journal entries each month. Larger grocery chains might have multiple deliveries a week, and multiple entries for purchases from a variety of suppliers on their accounts payable weekly.

This similarity extends to other retailers, from clothing stores to sporting goods to hardware. No matter the size of a business and no matter the product a business sells, the fundamental accounting entries remain the same.

While the general journal is useful in providing a record in time order of all accounting transactions of a business, it does not provide the account balance of a particular account. If a business is trying to determine the balance of a specific account, it would have to find all the journal entries affecting that account and then calculate a balance. Reviewing journal entries individually can be tedious and time consuming. To avoid doing this, the information recorded in the general journal is posted (or transferred) to a ledger, which is Step 3 of the Accounting Cycle: post journal information to the ledger.

Ledger

A ledger is a record of each account and its balance. While most businesses have various types of ledgers containing different accounts, the most basic type of ledger in practice is the general ledger. The general ledger is simply a collection of all T-accounts for a business, providing both the activity and balances of all accounts within the business. Posting refers to the process of transferring data from the journal to the general ledger. It is important to understand that T-accounts are only used for illustrative purposes in a textbook, classroom, or business discussion. They are not official accounting forms. Businesses will use ledgers for their official books, not T-accounts. The general ledger is helpful in that a business can easily extract account and balance information.

When calculating balances in ledger accounts, one must take into consideration which side of the account increases and which side decreases. To find the account balance, you must find the difference between the sum of all figures on the side that increases and the sum of all figures on the side that decreases. For example, the Cash account is an asset. We know from the accounting equation that assets increase on the debit side and decrease on the credit side. If there was a debit of $5,000 and a credit of $3,000 in the Cash account, we would find the difference between the two, which is $2,000 (5,000 – 3,000). The debit is the larger of the two sides ($5,000 on the debit side as opposed to $3,000 on the credit side), so the Cash account has a debit balance of $2,000.

Another example is a liability account, such as Accounts Payable, which increases on the credit side and decreases on the debit side. If there were a $4,000 credit and a $2,500 debit, the difference between the two is $1,500. The credit is the larger of the two sides ($4,000 on the credit side as opposed to $2,500 on the debit side), so the Accounts Payable account has a credit balance of $1,500.

We will show an example of transactions and how they are transferred from the journal and posted to the ledger in an example later in the chapter. In discussing the journalising and posting process above, procedures have been put in place to ensure that the double entry rule is followed – that is, the total amount of debit entries equals the total amount of the credit entries in both the general journal and general ledger accounts. By doing this, we will ensure that the accounting equation remains in balance and errors are minimised. However the procedure of ensuring total debits equal total credits do not detect errors related to journalising or posting incorrectly in the accounting system. Such errors can be detected by preparing a trial balance, which is Step 4 of the Accounting Cycle, and this step involves proving the equality of the debit and credit balances in the accounts which will examine below.

Trial Balance

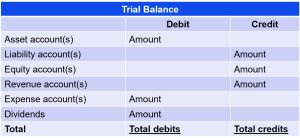

A trial balance is a listing of all accounts and their balances at a specific point in time. It lists the titles of all the accounts in a business’ general ledger in a column on the left, followed by the debit or credit balance of each account and the totals of the debit and credit columns. Asset accounts are usually listed first, followed by liability accounts, equity accounts and then revenue, expense and dividend accounts. A trial balance is prepared at the end of the period and is done so to assist in the preparation of the financial statements and to check the accuracy of the ledger or journal entries. It is important to note that the trial balance is unable to detect all recording errors. For example, if an expense paid of $500 is incorrectly recorded as $5000 both in the expense and cash accounts, both sides of the trial balance will still be equal. Thus care must be taken to check and confirm that the correct accounts and amounts are being recorded for each transaction.

Despite not being able to detect all errors, the trial balance serves three important functions. First it summarises in one place all accounts of a business and their respective balances, and it is from these balances that form the basis on which the financial statements are prepared. Second it proves that total debit balances equal total credit balances which means the accounting equation is in balance. If this is unequal, it means the accounting equation is out of balance and a correction would be needed. Lastly, a trial balance would be helpful in making any required adjustments to account balances at the end of the accounting period which will be illustrated in Chapter 3 Recording Adjusting Entries.

To prepare a trial balance, list the account numbers, names and their balances. Then total the debit and credit columns to determine their equality:

Let us now return to the 6 transactions of the startup mobile app developer, Kids Learn Online (KLO), that you analysed in AAA (please refer to p.38-41 of Chapter 2 of the AAA textbook) and how these transactions impacted the accounting equation. We will now record each of the transactions for KLO using Steps 2 to 4 of the Accounting Cycle and discuss how this impacts the financial statements in the next section.

Let us now return to the 6 transactions of the startup mobile app developer, Kids Learn Online (KLO), that you analysed in AAA (please refer to p.38-41 of Chapter 2 of the AAA textbook) and how these transactions impacted the accounting equation. We will now record each of the transactions for KLO using Steps 2 to 4 of the Accounting Cycle and discuss how this impacts the financial statements in the next section.