Calculate the break-even point

Mitchell Franklin; Patty Graybeal; Dixon Cooper; and Amanda White

Assumptions required for cost-volume-profit analysis

In a previous section, you learned how to determine and recognise the fixed and variable components of costs, and now you have learned about contribution margin. Those concepts can be used together to conduct cost-volume-profit (CVP) analysis, which is a method used by companies to determine what will occur financially if selling prices change, costs (either fixed or variable) change, or sales/production volume changes.

It is important, first, to make several assumptions about operations in order to understand CVP analysis and the associated contribution margin income statement. However, while the following assumptions are typical in CVP analysis, there can be exceptions. For example, while we typically assume that the sales price will remain the same, there might be exceptions where a quantity discount might be allowed. Our CVP analysis will be based on these four (4) assumptions:

- Costs are linear and can clearly be designated as either fixed or variable. In other words, fixed costs remain fixed in total over the relevant range and variable costs remain fixed on a per-unit basis. For example, if a company has the capability of producing up to 1,000 units a month of a product given its current resources, the relevant range would be 0 to 1,000. If they decided that they wanted to produce 1,800 units a month, they would have to secure additional production capacity. While they might be able to add an extra production shift and then produce 1,800 units a month without buying an additional machine that would increase production capacity to 2,000 units a month, companies often have to buy additional production equipment to increase their relevant range. In this example, the production capacity between 1,800 and 2,000 would be an expense that currently would not provide additional contribution toward fixed costs.

- Selling price per unit remains constant and does not increase or decrease based on volume (i.e., customers are not given discounts based on quantity purchased).

- In the case of manufacturing businesses, inventory does not change because we make the assumption that all units produced are sold.

- In the case of a company that sells multiple products, the sales mix remains constant. For example, if we are a beverage supplier, we might assume that our beverage sales are 3 units of coffee pods and two units of tea bags.

Using these assumptions, we can begin our discussion of CVP analysis with the break-even point.

Basics of the break-even point

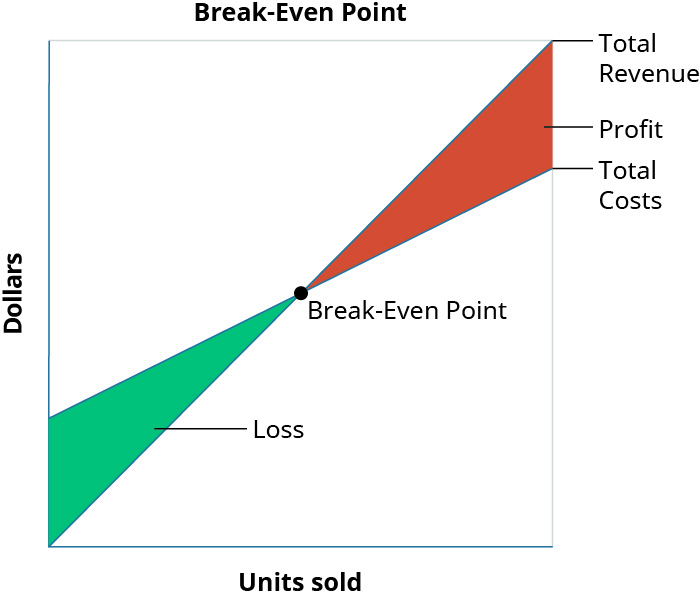

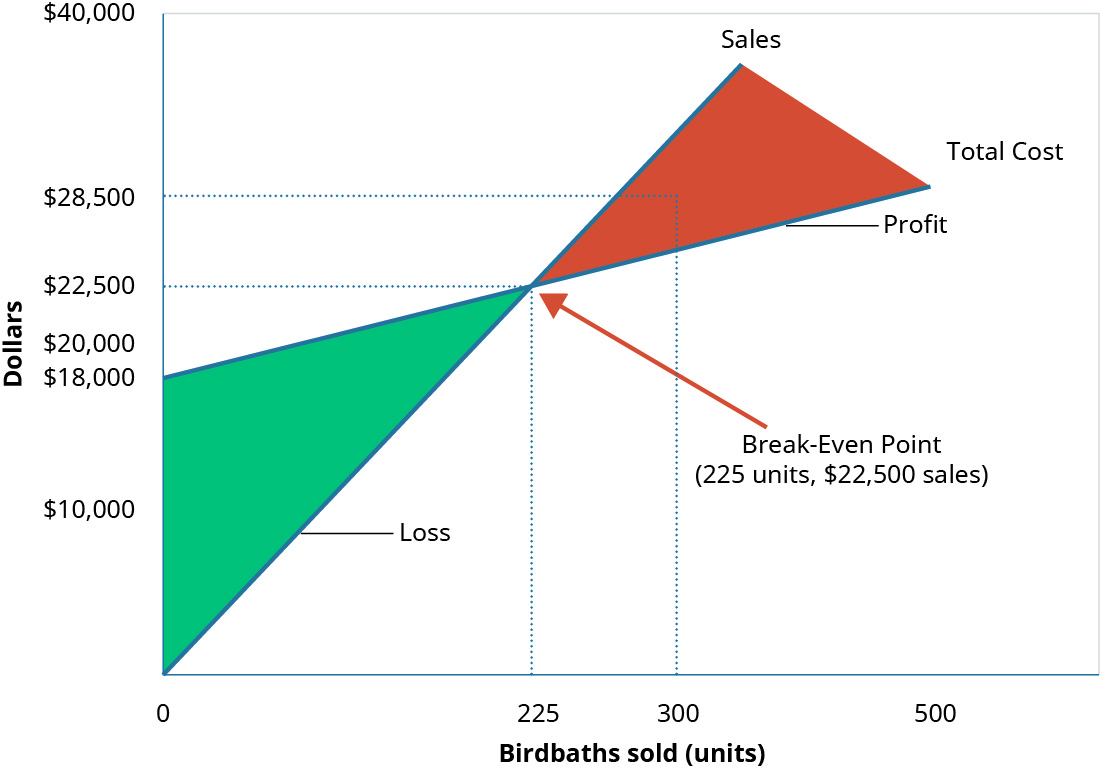

The break-even point is the dollar amount (total sales dollars) or production level (total units produced) at which the company has recovered all variable and fixed costs. In other words, no profit or loss occurs at break-even because Total Cost = Total Revenue. (Figure) illustrates the components of the break-even point:

The basic theory illustrated in the diagram above is that, because of the existence of fixed costs in most production processes, in the first stages of production and subsequent sale of the products, the company will report a loss. For example, assume that in an extreme case the company has fixed costs of $20,000, a sales price of $400 per unit and variable costs of $250 per unit, and it sells no units. It would realize a loss of $20,000 (the fixed costs) since it recognised no revenue or variable costs. This loss explains why the company’s cost graph recognised costs (in this example, $20,000) even though there were no sales. If it subsequently sells units, the loss would be reduced by $150 (the contribution margin) for each unit sold. This relationship will be continued until we reach the break-even point, where total revenue equals total costs. Once we reach the break-even point for each unit sold the company will see an increase in profits of $150.

For each additional unit sold, the loss typically is lessened until it reaches the break-even point. At this stage, the company is theoretically making neither a profit nor a loss – hence the term “break-even”. After the next sale beyond the break-even point, the company will begin to make a profit, and the profit will continue to increase as more units are sold. While there are exceptions and complications that could be incorporated, these are the general guidelines for break-even analysis.

As you can imagine, the concept of the break-even point applies to every business endeavor—manufacturing, retail, and service. Because of its universal applicability, it is a critical concept to managers, business owners, and accountants. When a company first starts out, it is important for the owners to know when their sales will be sufficient to cover all of their fixed costs and begin to generate a profit for the business. Larger companies may look at the break-even point when investing in new machinery, plants, or equipment in order to predict how long it will take for their sales volume to cover new or additional fixed costs. Since the break-even point represents that point where the company is neither losing nor making money, managers need to make decisions that will help the company reach and exceed this point as quickly as possible. No business can operate for very long below break-even. Eventually the company will suffer losses so great that they are forced to close their doors.

Break-even analysis and profitability

The first step in determining the viability of the business decision to sell a product or provide a service is analysing the true cost of the product or service and the timeline of payment for the product or service. Ethical managers need an estimate of a product or service’s cost and related revenue streams to evaluate the chance of reaching the break-even point.

Determining an accurate price for a product or service requires a detailed analysis of both the cost and how the cost changes as the volume increases. This analysis includes the timing of both costs and receipts for payment, as well as how these costs will be financed. An example is an IT service contract for a corporation where the costs will be frontloaded. When costs or activities are frontloaded, a greater proportion of the costs or activities occur in an earlier stage of the project. An IT service contract is typically employee cost intensive and requires an estimate of at least 120 days of employee costs before a payment will be received for the costs incurred. An IT service contract for $100,000 in monthly services with a 30% profit margin will require 4 months of upfront financing of $280,000 balanced over the four months before a single payment is received.

The overall profit at a specific point in time requires a careful determination of all of the costs associated with creating and selling the product or providing the service. An ethical managerial accountant will provide a realistic cost estimate, regardless of management’s desire to sell a product or provide a service. What might be a lucrative product on its face needs additional analysis provided by the managerial accountant.

To illustrate the concept of break-even, we will return to Leung Manufacturing and look at the Rosella birdbath they manufacture and sell.

Sales where net profit is $0

Leung Manufacturing is interested in finding out the point at which they break even selling their Rosella Model birdbath. They will break even when the operating income is $0. The operating income is determined by subtracting the total variable and fixed costs from the sales revenue generated by an enterprise. In other words, the managers at Leung want to know how many Rosella birdbaths they will need to sell in order to cover their fixed expenses and break even. Information on this product is:

|

Leung Manufacturing Rosella Model – for the year ending 30 June 2022

|

|

| Sales Price per Unit | $100 |

| Variable Cost per Unit | $20 |

| CONTRIBUTION MARGIN per Unit | $80 |

| Total Fixed Costs per Month | $18,000 |

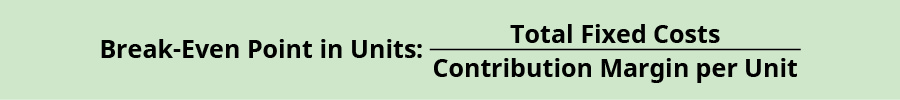

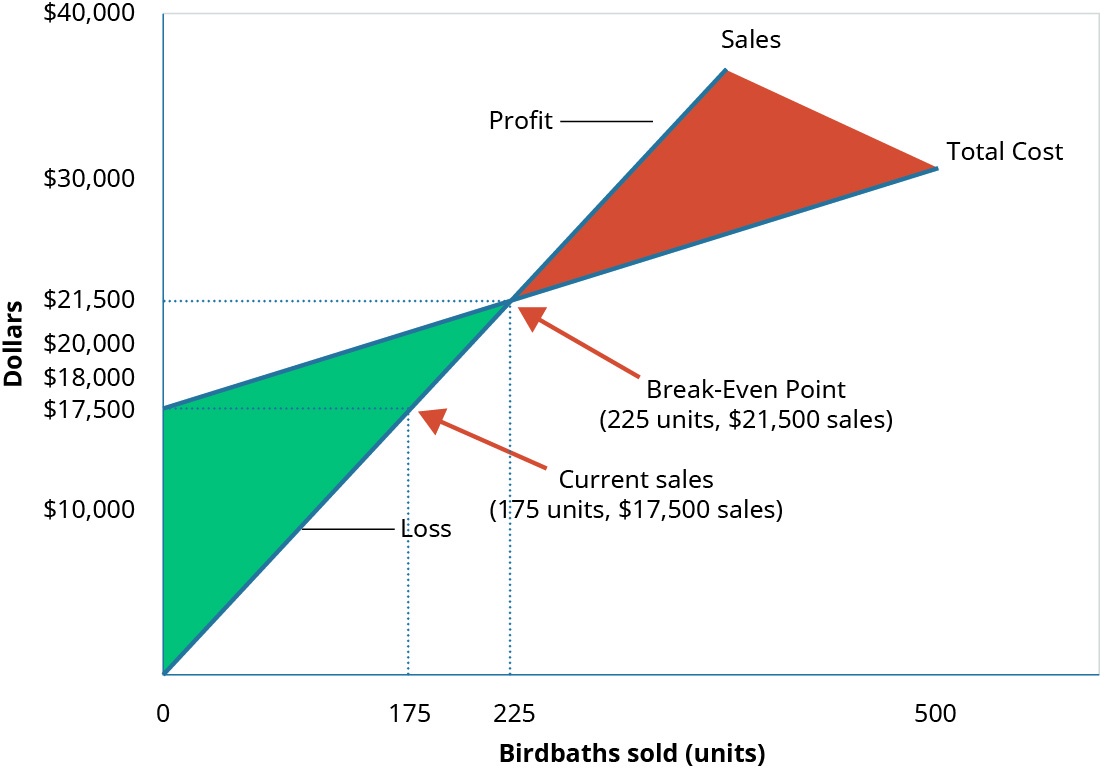

In order to find their break-even point, we will use the contribution margin for the Rosella and determine how many contribution margins we need in order to cover the fixed expenses, as shown in the formula in (Figure).

Applying this to Leung calculates as:

What this tells us is that Leung must sell 225 Rosella Model birdbaths in order to cover their fixed expenses. In other words, they will not begin to show a profit until they sell the 226th unit. This is illustrated in their contribution margin income statement.

|

Leung Manufacturing |

|

| Sales (225 units x $100 sales price) | $22,500 |

| Variable Costs (225 units x $20 VC) | $4,500 |

| CONTRIBUTION MARGIN | $18,000 |

| Fixed Costs | $18,000 |

| NET PROFIT | $0 |

The break-even point for Leung Manufacturing at a sales volume of $22,500 (225 units) is shown graphically in the diagram below.

As you can see, when Leung Manufacturing sells 225 Rosella Model birdbaths, they will make no profit, but will not suffer a loss because all of their fixed expenses are covered. However, what happens when they do not sell 225 units? If that happens, the business will make a net loss.

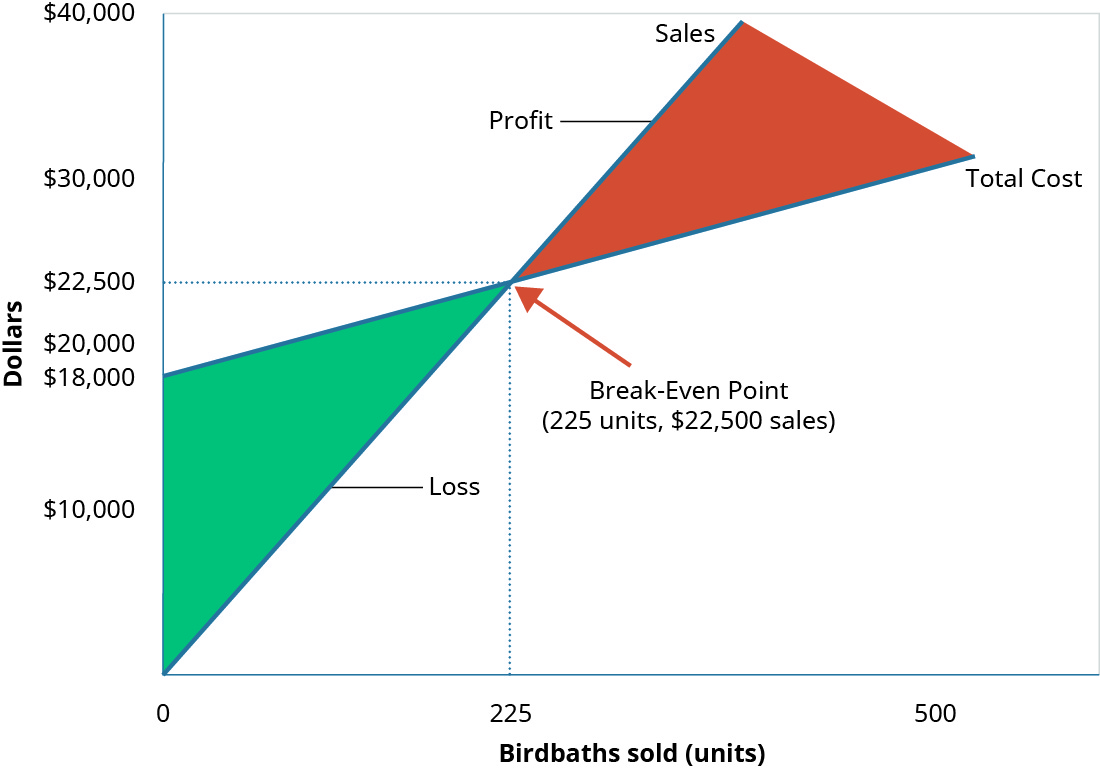

Sales where a loss is made (profit is negative)

In a recent month, local flooding caused Leung to close for several days, reducing the number of units they could ship and sell from 225 units to 175 units. The information in the table below reflects this drop in sales.

|

Leung Manufacturing |

|

| Sales (175 units x $100 sales price) | $17,500 |

| Variable Costs (1775 units x $20 VC) | $3,500 |

| CONTRIBUTION MARGIN | $14,000 |

| Fixed Costs | $18,000 |

| NET PROFIT (LOSS) | ($4000) |

At 175 units ($17,500 in sales), Leung does not generate enough sales revenue to cover their fixed expenses and they suffer a loss of $4,000. They did not reach the break-even point of 225 units.

Sales where net profit is positive

What happens when Leung has a busy month and sells 300 Rosella birdbaths? We have already established that the contribution margin from 225 units will put them at break-even. When sales exceed the break-even point the unit contribution margin from the additional units will go toward profit. This is reflected on their income statement.

|

Leung Manufacturing |

|

| Sales (300 units x $100 sales price) | $30,000 |

| Variable Costs (300 units x $20 VC) | $6,000 |

| CONTRIBUTION MARGIN | $24,000 |

| Fixed Costs | $18,000 |

| NET PROFIT | $6,000 |

Again, looking at the graph for break-even below, you will see that their sales have moved them beyond the point where total revenue is equal to total cost and into the profit area of the graph.

Leung Manufacturing can use the information from these different scenarios to inform many of their decisions about operations, such as sales goals.

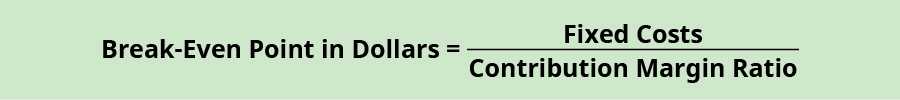

However, using the contribution margin per unit is not the only way to determine a break-even point. Recall that we were able to determine a contribution margin expressed in dollars by finding the contribution margin ratio. We can apply that contribution margin ratio to the break-even analysis to determine the break-even point in dollars. For example, we know that Leung had $18,000 in fixed costs and a contribution margin ratio of 80% for the Rosella model. We will use this ratio to calculate the break-even point in dollars.

Applying the formula to Leung gives this calculation:

Leung Manufacturing will have to generate $22,500 in monthly sales in order to cover all of their fixed costs. In order for us to verify that Leung’s break-even point is $22,500 (or 225 units) we will look again at the contribution margin income statement at break-even:

|

Leung Manufacturing |

|

| Sales (225 units x $100 sales price) | $22,500 |

| Variable Costs (225 units x $20 VC) | $4,500 |

| CONTRIBUTION MARGIN | $18,000 |

| Fixed Costs | $18,000 |

| NET PROFIT | $0 |

By knowing at what level sales are sufficient to cover fixed expenses is critical, but companies want to be able to make a profit and can use this break-even analysis to help them.

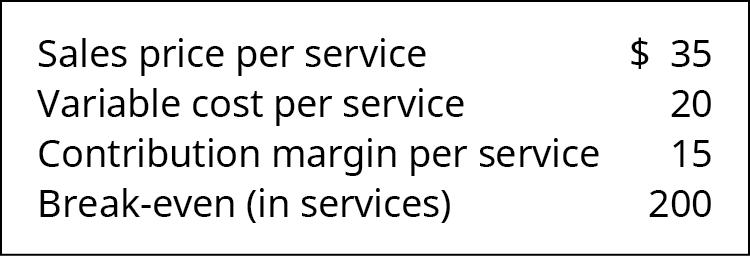

Example – the cost of a haircut

You are the manager of a hair salon and want to know how many ladies’ haircuts your salon needs to sell in a month in order to cover the fixed costs of running the salon. You have determined that, at the current price of $35 per haircut, you have $20 in variable costs associated with each cut. These variable costs include stylist wages, hair product, and shop supplies. Your fixed costs are $3,000 per month. You perform a break-even analysis on a per-unit basis and discover the following:

You have 4 stylists plus yourself working in the salon and are open 6 days per week. Considering the break-even point and the number of available stylists, will the salon ever break even? If it does, what will need to happen? What can be done to achieve the break-even point?

Examples of the effects of variable and fixed costs in determining the break-even point

Companies typically do not want to simply break even, as they are in business to make a profit. Break-even analysis also can help companies determine the level of sales (in dollars or in units) that is needed to make a desired profit. The process for factoring a desired level of profit into a break-even analysis is to add the desired level of profit to the fixed costs and then calculate a new break-even point. We know that Leung Manufacturing breaks even at 225 Rosella birdbaths, but what if they have a target profit for the month of July? They can simply add that target to their fixed costs. By calculating a target profit, they will produce and (hopefully) sell enough bird baths to cover both fixed costs and the target profit.

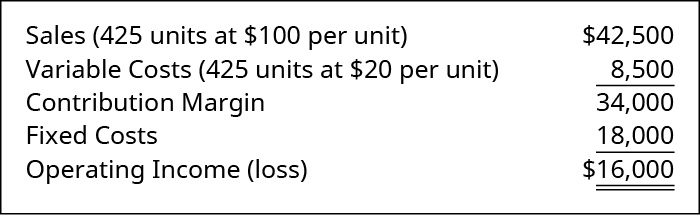

If Leung wants to earn $16,000 in profit in the month of June, we can calculate their new break-even point as follows:

= (18,000 + 16,000) / 80

= 425 units

= (18,000 + 16,000) / 0.8

= $42,500

Note – when you use the Contribution Margin in dollars, the output is in units. When you use the Contribution Margin Ratio, the output is in dollars.

As done previously, we can confirm this calculation using the contribution margin income statement:

Application of break-even concepts for a service organisation

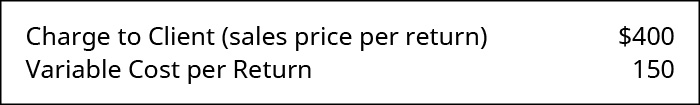

Because break-even analysis is applicable to any business enterprise, we can apply these same principles to a service business. For example, Marshall & Hirito is a mid-sized accounting firm that provides a wide range of accounting services to its clients but relies heavily on personal income tax preparation for much of its revenue. They have analysed the cost to the firm associated with preparing these returns. They have determined the following cost structure for the preparation of a standard Individual Income Tax Return:

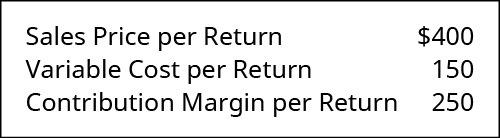

They have fixed costs of $14,000 per month associated with the salaries of the accountants who are responsible for preparing the tax return In order to determine their break-even point, they first determine the contribution margin for tax return preparation as shown:

Now they can calculate their break-even point:

= $14,000 / 250

= 56 tax returns

Remember, this is the break-even point in units (the number of tax returns) but they can also find a break-even point expressed in dollars by using the contribution margin ratio. First, they find the contribution margin ratio. Then, they use the ratio to calculate the break-even point in dollars:

= $14,000 / 0.625

= $22,400

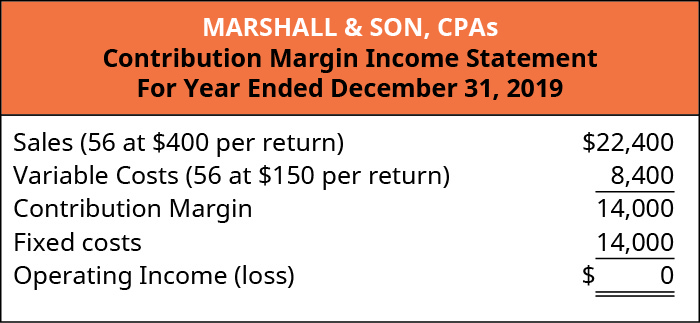

We can confirm these figures by preparing a contribution margin income statement:

Therefore, as long as Marshall & Hirito prepares 56 tax returns, they will earn no profit but also incur no loss. What if Marshall & Hirito has a target monthly profit of $10,000? They can use the break-even analysis process to determine how many returns they will need to prepare in order to cover their fixed expenses and reach their target profit:

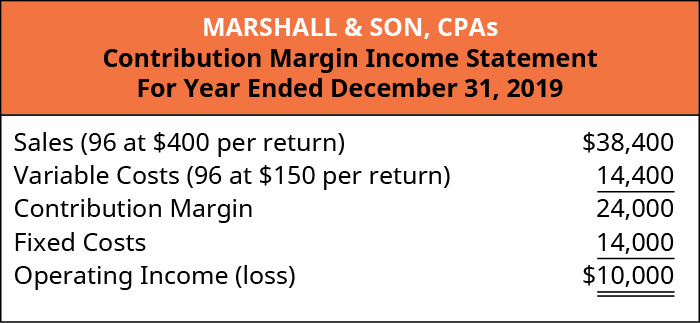

= (14,000 + 10,000) / 250

= 96 units (or tax returns)

They will need to prepare 96 returns during the month in order to realize a $10,000 profit. Expressing this in dollars instead of units requires that we use the contribution margin ratio as shown:

= (14,000 + 10,000) / 0.625

= $38,400

Marshall & Hirito now knows that, in order to cover the fixed costs associated with this service, they must generate $38,400 in revenue. Once again, let’s verify this by constructing a contribution margin income statement:

As you can see, the $38,400 in revenue will not only cover the $14,000 in fixed costs, but will supply Marshall & Hirito with the $10,000 in profit (net income) they desire.

As you’ve learned, break-even can be calculated using either contribution margin per unit or the contribution margin ratio. Now that you have seen this process, let’s look at an example of these two concepts presented together to illustrate how either method will provide the same financial results.

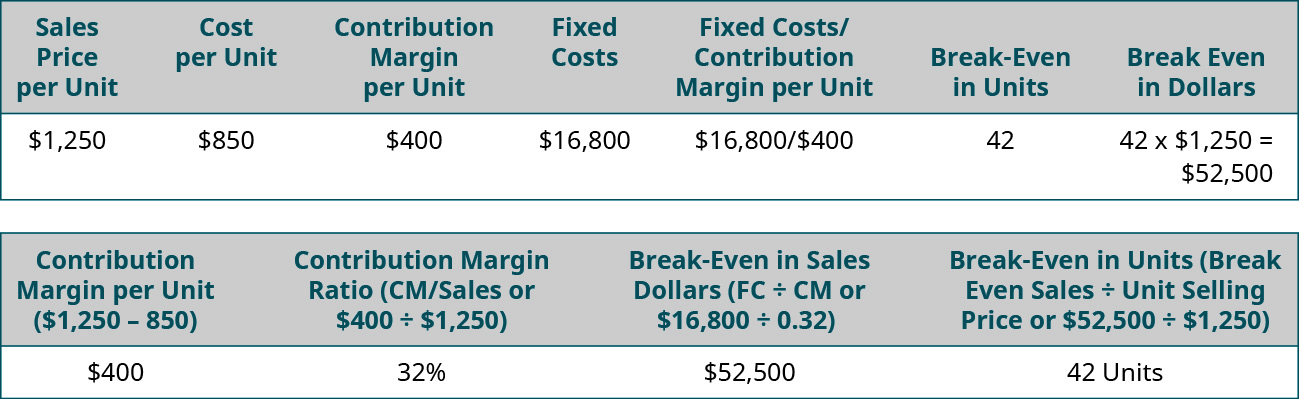

Suppose that Channing’s Chairs designs, builds, and sells unique ergonomic desk chairs for home and business. Their bestselling chair is the Spine Saver. (Figure) illustrates how Channing could determine the break-even point in sales dollars using either the contribution margin per unit or the contribution margin ratio.

Note that in either scenario, the break-even point is the same in dollars and units, regardless of approach. Thus, you can always find the break-even point (or a desired profit) in units and then convert it to sales by multiplying by the selling price per unit. Alternatively, you can find the break-even point in sales dollars and then find the number of units by dividing by the selling price per unit.

What about incorporating taxes?

So far, we have conducted all of our analysis excluding tax. Tax rates for incorporated business in Australia is 30% (Australian Taxation Office). Therefore, to calculate net profit AFTER tax, we simply deduct 30% from pre-tax net profit in taxes.

We can also incorporate taxes into our Target Profit figure when conducting CVP sensitivity analysis. For example, if a business desires to make $150,500 in profit AFTER tax, then we need to calculate their desired or target profit BEFORE tax. This would be calculated by dividing $150,500 by 70 and multiplying by 100. This is because $150,000 represents 70% of net profit before tax. The desired pre-tax profit would be $215,000.