Making decisions when resources are scarce or limited

Mitchell Franklin; Patty Graybeal; Dixon Cooper; and Amanda White

Understanding the importance of capacity

Companies use various resources to be productive. These resources, which include time, labour, space, and machines, are limited, thus constraining the ability of a company to have unlimited productive capacity. For example, a retail store is constrained by the amount of floor space available to display its goods, while a law office may be constrained by the number of hours the paralegal team can feasibly work. These constraints require companies to make decisions on the best ways to allocate their resources in a way that maximises the benefit to the firm. This situation is especially true when a company is operating at capacity or makes multiple products or provides multiple services.

The question as to which products and how many should be made is a common constraint problem. For example, consider a business that runs at capacity, making four products by running two eight-hour shifts per day, seven days a week for 50 weeks per year. This business is limited to 5,600 working hours per year (8 hr. shifts × 2 shifts × 7 days per week × 50 weeks) unless a third shift is added. Adding a third shift may be prohibitive for any number of reasons, including local ordinances that prevent operating twenty-four hours a day, Environmental Protection Agency constraints, or the down-time of the machines that is required several hours a day for maintenance and calibration. What is the best way for this company to use these work hours? Which products should it produce first and how many of each should it produce?

These types of situations constrain, or limit, management’s ability to use their facilities and workforce. Having limited availability of a resource, such as time, labour, or machine hours means that item becomes a scarce resource. A constraint is a scarce resource that limits the output or productive capacity of the organisation.

Ordinarily, there are very few actual constraints in any process. Sometimes, there is only one. However, the existence of a constraint can have a major effect on the productivity of an organisation. This fact applies to all types of entities, such as production facilities or service providers. One way to view this issue is to consider the old cliché that a chain is only as strong as its weakest link. In the example, when trying to measure or estimate a business’s maximum efficiency, its results will often be reduced by the overall negative effects of the constraints. When the constraint slows production, it is called a bottleneck. Managers are often faced with the problem of deciding how to best use a scarce resource to prevent bottlenecks. Under the constraint of limited resources, how do managers make decisions when they are working within these conditions?

Fundamentals of how to make decisions when resources are constrained

As with other short-term decisions, a company must consider the relevant costs and revenues when making decisions when resources are constrained. Whether the business facing a constraint is a merchandising, manufacturing, or service organisation, the initial step in allocating scarce or constrained resources is to determine the unit contribution margin, which is the selling price per unit minus the variable cost per unit, for each product or service. The company should produce or provide the products or services that generate the highest contribution margin first, followed by those with the second highest, and so forth. The total contribution margin will be maximised by promoting those products or accepting those orders with the highest contribution margin in relation to the scarce resource. In other words, products or services should be ranked based on their unit contribution margin per production restraint, which is the unit contribution margin divided by the production restraint.

If constraints are not managed, a bottleneck usually results, meaning that production slows and a back-up occurs at stages prior to the bottleneck. For example, in producing boxes of cereal, if the cereal is produced at a rate of 1,000 grams per minute but the bagging machines can only bag 800 grams per minute, this will create a bottleneck. Similarly, if on a Saturday morning before a football grand final, the local supermarket and bottle shop has ten checkout lanes but only opens four of them, long lines will result from the constraint of too few checkout lanes available during a rush of customers. Management must decide how many scarce resources (employees, in this example) to pull from stocking the shelves to working at cash registers. It may be difficult to see how bottlenecks affect profitability, and they appear to be more of a timing or throughput issue. But bottlenecks can affect profitability in a number of ways.

Bottlenecks at the supermarket can result in customers leaving to store shop elsewhere or can negatively affect the reputation of the store, which can impact future sales. In the cereal example, bottlenecks in the packaging area can slow the delivery of boxes of cereal to distributors and individual stores. Poor or inconsistent delivery may drive customers to purchase from other cereal manufacturers, which would have a definite impact on profitability.

A common problem relating to constraints occurs in multi-product production environments. Management will need to evaluate the constraints to determine the best mix of products that will minimise the effects of the constraints. In addition to making sure that the best product mix is chosen, managers should seek ways to increase the effective capacity of the constraint. Conceptually, there are two ways a company can do this: increase the rate of output at the bottleneck, or increase the time available at the bottleneck. Increasing the capacity of the constraint or bottleneck is also called relaxing the constraint or elevating the constraint. Some specific examples of ways to relax the constraint include:

- Keep the production facilities open longer hours. This may allow the work-flow through the bottleneck area to be slowed and thus prevent the bottleneck from occurring. However, this may require paying workers overtime pay.

- If working extra hours is not a viable option, then moving additional workers to the bottleneck area may be beneficial as long as the areas from which they were moved are adequately covered and additional problem areas do not result.

- Instead of using current workers, additional staff may be hired to smooth the work flow through the bottleneck area.

- Outsource some or all of the work in the area of the bottleneck. It may be cheaper and more cost effective to buy parts of components than to slow production due to the bottleneck.

- Redesign the production process to prevent the bottleneck by adding more resources to eliminate the bottleneck, re-organising the process to distribute the bottleneck-causing activities to different parts of the production process, or managing processing times at other stages prior to the bottleneck to help prevent the bottleneck form occurring.

- Insuring a minimal number of defects and rework, since they typically slow the production process and thus add to the bottleneck.

Preventing and minimising bottlenecks can have significant benefits to the bottom line (profitability) of the company. The reduction of bottlenecks allows the company to move more products through the production phase and thus be ready to sell.

When to include a lifesaving option: the case of the Ford Pinto

The case of the fiery Ford Pinto demonstrates that more than cost and revenue should be considered when making an ethical business decision.

(CC0)

In the early 1970s, the Ford Motor Company set out to build a Pinto for less than $2,000. Cars were much less expensive then, and Ford had to determine whether or not to include a component part that cost around $10. Given the high cost, Ford decided not to include the component, a rubber bladder for the fuel tank. However, in rear-end collisions at over 21 miles per hour, the rubber bladder component functions to prevent the gas tank from flooding the interior of the car with petrol and fumes. Because of the decision not to include the component, a number of Pintos involved in collisions exploded into flames, injuring and sometimes killing the occupants.

Although Ford was aware of the defect, the company’s cost/benefit analysis indicated it was less expensive to build Pintos without the rubber bladder, even when including expected reimbursement costs for anyone injured or killed. However, the decision to allow a defective product to be built in order to reduce overall costs caused a significant hit to Ford’s reputation. Ultimately, the litigation costs for knowingly constructing a defective car were higher than the original cost of including the rubber bladder component. While Ford’s decision seemed profitable in the short-term, their financial analysis could have been improved if it also took into account long-term impacts.

Example – Wood World

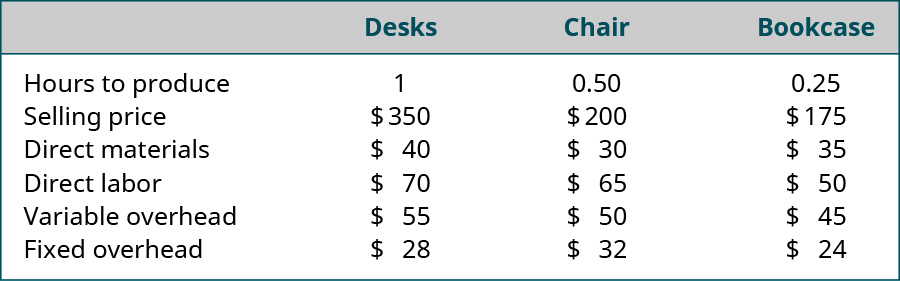

Wood World, Inc., produces wooden desks, chairs, and bookcases. These items are produced using the same machines, and there is a maximum of 80,000 machine-hours available during the year. The information about the production time and costs for these three items is:

Wood World is limited in producing its products by the number of possible machine-hours. Orders have been received for 60,000 desks, 48,000 chairs, and 40,000 bookcases, which will require 94,000 machine-hours to produce. Since there are not enough machine-hours available to fill all of the orders, which orders should Wood World fill first?

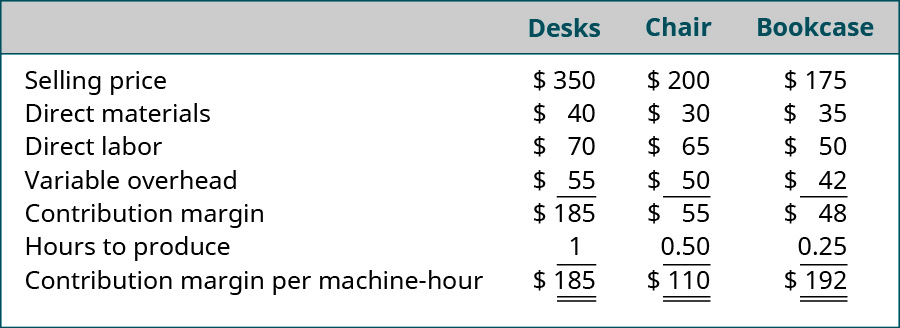

Wood World example – working out

To address this question, Wood World must find the contribution margin per machine-hour since machine-hours are the constraining factor for production.

Final analysis of the decisions

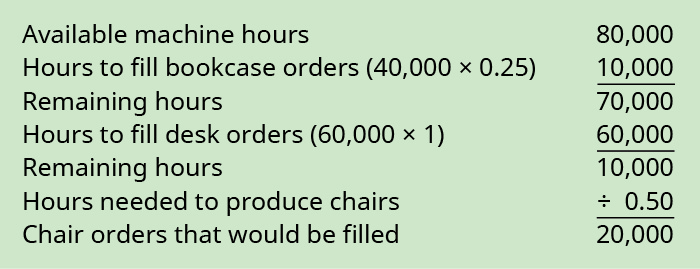

Wood World should fulfill the orders for bookcases first, desks second, and chairs last. The bookcases provide the highest contribution margin per machine-hour, followed by desks and then chairs. Maximising the contribution margin per constraint, in this case per machine-hour, is the best way for Wood World to manage the constraint. How many of each item will be produced?

Therefore, based on contribution margin and the constraint of machine hours, Wood World should fill all 40,000 of the bookcase orders first, then fill the 60,000 desk orders and, and fill 20,000 of the chair orders last.

Are there any qualitative issues that Wood World should consider? One concern may be that customers who typically buy a desk and chair together may not be able to do so if the chair production is affected by a bottleneck. Another qualitative issue in keeping with the furniture example is that a company might find producing dining room tables to be significantly more profitable than matching chairs or matching cupboards. However, they will still be required to produce the less profitable chairs and cupboards, because many consumers will want to buy all three items as a set.

The benefits of effectively managing constraints can be enormous. Managers need to understand the positive impact effective management of constrained resources can have on the company’s bottom line. The contribution margin per unit of the scarce resource can be used to assess the value of relaxing the constraint. When there is unsatisfied demand for a single product because of a constraint, the value of additional time on the constraint is simply the contribution margin per unit of the scarce resource for that product. When there are two or more products with unsatisfied demand, the value of additional time on the bottleneck would be the largest contribution margin per unit of the scarce resource for any product whose demand is unsatisfied. In many situations, when dealing with conflicting time constraints an evaluation of multiple bottlenecks might identify a viable solution. While many bottleneck issues and their solutions could be somewhat complex, others might be addressed more simply. For example, in some cases the problem might be solved by the addition of an additional work shift.