Contribution margin – the foundation for CVP

Mitchell Franklin; Patty Graybeal; Dixon Cooper; and Amanda White

Fixed costs, relevant range and variable costs

To be able to conduct Cost Volume Profit (CVP) analysis, we need to understand something called the contribution margin. However, before examining contribution margins, let’s review some key concepts: fixed costs, relevant range and variable costs.

Fixed costs are those costs that will not change within a given range of production. For example, in the current case, the fixed costs will be the student sales staff fee of $100. No matter how many shirts the club sells within the relevant range, the fee will be locked in at $100. The relevant range is the anticipated production activity level. Fixed costs remain constant within a relevant range. If production levels exceed expectations, then additional fixed costs will be required (eg have two stalls).

For example, assume that the Club is going to hire a people mover van to get students to a weekend study camp. A people-mover van like a Toyota HiAce People mover will hold twelve passengers, at a cost of $200 per van. If they send one to twelve participants, the fixed cost for the van would be $200. If they send thirteen to twenty four students, the fixed cost would be $400 because they will need two vans. We would consider the relevant range to be between one and twelve passengers, and the fixed cost in this range would be $200. If they exceed the initial relevant range, the fixed costs would increase to $400 for thirteen to twenty four passengers.

Variable costs are those costs that vary per unit of production. Direct materials are often typical variable costs, because you normally use more direct materials when you produce more items. In our example, if the students sold 100 shirts, assuming an individual variable cost per shirt of $10, the total variable costs would be $1,000 (100 × $10). If they sold 250 shirts, again assuming an individual variable cost per shirt of $10, then the total variable costs would $2,500 (250 × $10).

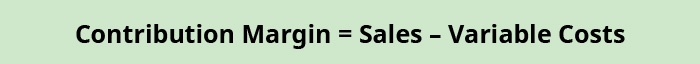

Defining the contribution margin

Contribution margin is the amount by which a product’s selling price exceeds its total variable cost per unit. This difference between the sales price and the per unit variable cost is called the contribution margin because it is the per unit contribution toward covering the fixed costs. It typically is calculated by comparing the sales revenue generated by the sale of one item versus the variable cost of the item:

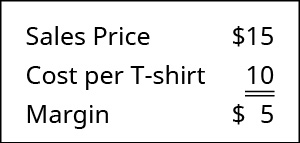

In our example, the sales revenue from one shirt is $15 and the variable cost of one shirt is $10, so the individual contribution margin is $5. This $5 contribution margin is assumed to first cover fixed costs first and then any contribution after fixed costs are covered can be considered profit.

As you will see, it is not just small operations, such as the Business Students Club scenario provided in the previous section, that benefit from cost-volume-profit (CVP) analysis. At some point, all businesses find themselves asking the same basic questions: How many units must be sold in order to reach a desired income level? How much will each unit cost? How much of the sales price from each unit will help cover our fixed costs?

For example, Starbucks faces these same questions every day, only on a larger scale. When they introduce new menu items, such as seasonal specialty drinks, they must determine the fixed and variable costs associated with each item. Adding menu items may not only increase their fixed costs in the short run (via advertising and promotions) but will bring new variable costs. Starbucks needs to price these drinks in a way that covers the variable costs per unit and additional fixed costs and contributes to overall net income. Regardless of how large or small the enterprise, understanding how fixed costs, variable costs, and volume are related to income is vital for sound decision-making.

(credit: modification of “StarbucksVaughanMills” by “Raysonho”/Wikimedia Commons, CC0)

Understanding how to use fixed costs, variable costs, and sales in CVP analyses requires an understanding of the term margin. You may have heard that restaurants and supermarkets have very low margins, while jewellery stores and furniture stores have very high margins. What does “margin” mean? In the broadest terms, margin is the difference between a product or service’s selling price and its cost of production. Recall the accounting club’s T-shirt sale. The difference between the sales price per T-shirt and the purchase price of the T-shirts was the accounting club’s margin:

Recall that in the previous section, we explained the characteristics of fixed and variable costs and introduced the basics of cost behavior. Let’s now apply these behaviors to the concept of contribution margin. The company will use this “margin” to cover fixed expenses and hopefully to provide a profit. There are multiple ways to analyse the contribution margin

- by unit of production

- as a ratio

- in total.

Let’s begin by examining contribution margin on a per unit basis.

Unit Contribution Margin

When the contribution margin is calculated on a per unit basis, it is referred to as the contribution margin per unit or unit contribution margin. You can find the contribution margin per unit using the equation shown below:

It is important to note that this unit contribution margin can be calculated either in dollars or as a percentage. To demonstrate this principle, let’s consider the costs and revenues of Leung Manufacturing, a small company that manufactures and sells birdbaths to specialty retailers. The birdbaths are named after recognisable Australian birds such as the Rosella and the Cockatoo.

Leung Manufacturing sells its Rosella Model for $100 and incurs variable costs of $20 per unit. In order to calculate their per unit contribution margin, we use the formula in the table below to determine that on a per unit basis, their contribution margin is:

|

Leung Manufacturing ROSELLA Model for year ending 30 June 2022 |

|

| Sales price per unit | $100 |

| – Variable cost per unit | $20 |

| = Contribution margin per unit | $80 |

This means that for every Rosella model they sell, they will have $80 to contribute toward covering fixed costs, such as rent, insurance, and manager salaries.

But Leung Manufacturing manufactures and sells more than one model of birdbath. They also sell a Cockatoo Model for $75, and these birdbaths incur variable costs of $15 per unit. For the Cockatoo Model, their contribution margin on a per unit basis is the $75 sales price less the $15 per unit variable costs is as follows:

|

Leung Manufacturing COCKATOO Model for year ending 30 June 2022 |

|

| Sales price per unit | $75 |

| – Variable cost per unit | $15 |

| = Contribution margin per unit | $60 |

This demonstrates that, for every Cockatoo model they sell, they will have $60 to contribute toward covering fixed costs and, if there is any left, toward profit. Every product that a company manufactures or every service a company provides will have a unique contribution margin per unit.

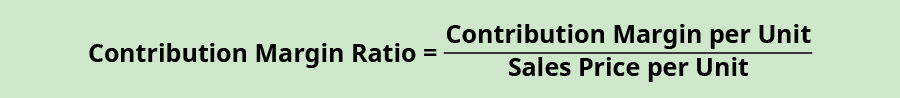

In these examples, the contribution margin per unit was calculated in dollars per unit, but another way to calculate contribution margin is as a ratio (percentage).

Contribution Margin Ratio

The contribution margin ratio (CMR) is the percentage of a unit’s selling price that exceeds total unit variable costs. In other words, contribution margin is expressed as a percentage of sales price and is calculated using this formula:

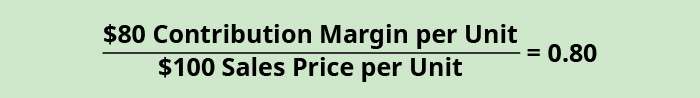

For Leung Manufacturing and their ROSELLA Model, the contribution margin ratio will be

At a contribution margin ratio of 80%, approximately $0.80 of each sales dollar generated by the sale of a Rosella Model is available to cover fixed expenses and contribute to profit. The contribution margin ratio for the birdbath implies that, for every $1 generated by the sale of a Rosella Model, they have $0.80 that contributes to fixed costs and profit. Thus, 20% of each sales dollar represents the variable cost of the item and 80% of the sales dollar is margin. Just as each product or service has its own contribution margin on a per unit basis, each has a unique contribution margin ratio. Although this process is extremely useful for analysing the profitability of a single product, good, or service, managers also need to see the “big picture” and will examine contribution margin in total across all products, goods, or services.

Another example of contribution margin

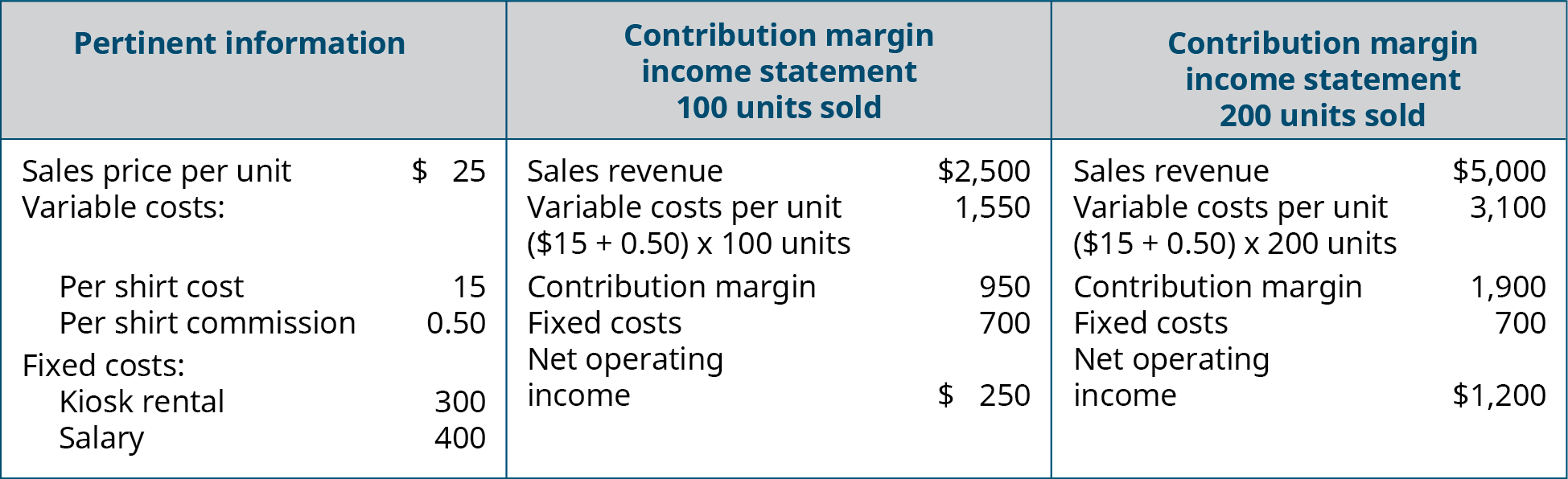

You rent a kiosk (a free standing stall) in the local shopping centre for $300 a month and use it to sell T-shirts with sporting team logos from all over the world. You sell each T-shirt for $25, and your cost for each shirt is $15 (including appropriate licensing and royalty fees for using the sporting team logos). You also pay your sales person a commission of $0.50 per T-shirt sold in addition to a salary of $400 per month. Construct a contribution margin income statement for two different months: in one month, assume 100 T-shirts are sold, and in the other, assume 200 T-shirts are sold.

Solution

Total Contribution Margin

This “big picture” is gained by calculating total contribution margin – the total amount by which total sales exceed total variable costs. We calculate total contribution margin by multiplying per unit contribution margin by sales volume or number of units sold. This approach allows managers to determine how much profit a company is making before paying its fixed expenses. For Leung Manufacturing, if the managers want to determine how much their Rosella Model contributes to the overall profitability of the company, they can calculate total contribution margin as follows:

|

Leung Manufacturing ROSELLA Model for month ending 31 May 2022 |

|

| Units sold | 500 units |

| Contribution margin per unit | $80 |

| = Total contribution margin (500 x $80) | $40,000 |

For the month of May, sales from the Rosella Model contributed $40,000 toward fixed costs. Looking at contribution margin in total allows managers to evaluate whether a particular product is profitable and how the sales revenue from that product contributes to the overall profitability of the company. In fact, we can create a specialised income statement called a contribution margin income statement to determine how changes in sales volume impact the bottom line.

To illustrate how this form of income statement can be used, contribution margin income statements for Leung Manufacturing are shown for the months of May and June, where fixed costs are $23,000 per month.

In May, Leung sold 500 Rosella Models at $100 per unit, which resulted in the operating income shown on the contribution margin income statement:

|

Leung Manufacturing Contribution Margin Income Statement for month ending 31 May 2022 |

|

| Sales (500 units x $100/unit) | $50,000 |

| Less Variable costs (500 units x $20/unit) | $10,000 |

| CONTRIBUTION MARGIN | $40,000 |

| Less Fixed costs | $23,000 |

| Net profit | $17,000 |

In June, 750 of the Rosella models were sold. When comparing the two statements, take note of what changed and what remained the same from May to June.

|

Leung Manufacturing Contribution Margin Income Statement for month ending 30 June 2022 |

|

| Sales (750 units x $100/unit) | $75,000 |

| Less Variable costs (750 units x $20/unit) | $15,000 |

| CONTRIBUTION MARGIN | $60,000 |

| Less Fixed costs | $23,000 |

| Net profit | $37,000 |

Using this contribution margin format makes it easy to see the impact of changing sales volume on operating income. Fixed costs remained unchanged; however, as more units are produced and sold, more of the per-unit sales price is available to contribute to the company’s net income.

Before going further, let’s note several key points about CVP and the contribution margin income statement.

- First, the contribution margin income statement is used for internal purposes and is not shared with external stakeholders.

- Secondly, in this specialised profit and loss/income statement, when net profit is shown, it actually refers to net profit without regard to income taxes. Companies can also consider taxes when performing a CVP analysis to project both pre-tax and post-tax profit, however that is beyond the scope of this introductory course on accounting.

Why use three different methods to discuss contribution margin?

Regardless of whether contribution margin is calculated on a per-unit basis, calculated as a ratio, or incorporated into an income statement, all three express how much sales revenue is available to cover fixed expenses and contribute to profit. Let’s examine how all three approaches convey the same financial performance, although represented somewhat differently.

You will recall that the per-unit contribution margin was $80 for a Leung Rosella birdbath. When Leung sold 500 units in May, each unit contributed $80 to fixed expenses and profit.

Now, let’s use June’s Contribution Margin Income Statement as previously calculated to verify the contribution margin based on the contribution margin ratio previously calculated, which was 80%, by applying this formula:

June sales were $75,000. The Contribution Margin Ratio (CMR) is $0.80. Therefore,

Total Contribution Margin = Total Sales x CMR = $75,000 x $0.80 = $60,000.

This matches with the Contribution margin income statement for June shown above.

Regardless of how contribution margin is expressed, it provides critical information for managers. Understanding how each product, good, or service contributes to the business’s profitability allows managers to make decisions such as which product lines they should expand or which might be discontinued. When allocating scarce resources, the contribution margin will help them focus on those products or services with the highest margin, thereby maximising profits.

The evolution of Cost-Volume-Profit relationships

The CVP relationships of many organisations have become more complex recently because many labour-intensive jobs have been replaced by or supplemented with technology, changing both fixed and variable costs. For those organizations that are still labour-intensive, the labour costs tend to be variable costs, since at higher levels of activity there will be a demand for more labour usage. For example, assuming one worker is needed for every 50 customers per hour, we might need two workers for an average sales season, but during the Christmas season, the store might experience 250 customers per hour and thus would need five workers.

However, the growing trend in many segments of the economy is to convert labour-intensive enterprises (primarily variable costs) to operations heavily dependent on equipment or technology (primarily fixed costs). For example, in retail, many functions that were previously performed by people are now performed by machines or software, such as the self-checkout machines in stores such as Woolworths and Coles. Since machine and software costs are often depreciated or amortised, these costs tend to be the same or fixed, no matter the level of activity within a given relevant range.

In China, completely unmanned grocery stores have been created that use facial recognition for accessing the store. Patrons will shop, bag the purchased items, leave the store, and be billed based on what they put in their bags. Along with managing the purchasing process, inventory is maintained by sensors that let managers know when they need to restock an item.

In the United States, Amazon uses Amazon Go stores to offer the same service. Check out this video (copyright owned by CNET) for an example of an Amazon Go store. Note that there are currently 25 Amazon Go stores in the USA, but none in Australia or Asia.

In Australia, COVID19 accelerated the click-and-collect service offered by retailers. Customers can order online from most stores and have it ready to pick up in just a few hours (avoiding potentially long wait times for courier or postal delivery). In some instances, you don’t even need to enter the store. Woolworths offers a direct-to-boot service – order your items online and book a window to pick them up. When you arrive, click a button on the app or in the text message you received letting you know your groceries are ready – and someone will bring out your order and place it directly in your boot.

Another major innovation affecting labor costs is the development of driverless cars and trucks (primarily fixed costs), which will have a major impact on the number of taxi and truck drivers in the future (primarily variable costs). The first to be approved for use is the Nuro system in the USA (you can read more about Nuro in this article from CNET). Do these labour-saving processes change the cost structure for the company? Are variable costs decreased? What about fixed costs? Let’s look at this in more detail.

When ordering food through an app, there is no need to have an employee take the order, but someone still needs to prepare the food and package it for the customer. The variable costs associated with the wages of order takers will likely decrease, but the fixed costs associated with additional technology to allow for online ordering will likely increase. When grocery customers place their orders online, this not only requires increased fixed costs for the new technology, but it can also increase variable labor costs, as employees are needed to fill customers’ online orders. Many stores may move customer-facing positions to online order fulfillment rather than hiring additional employees. Other stores may have employees fill online grocery orders during slow or downtimes. Both Woolworths and Coles operate “dark stores” in Australia – stores that have no customers and are designed only for online order fulfilment.

Using driverless cars and trucks decreases the variable costs tied to the wages of the drivers but requires a major investment in fixed-cost assets – the autonomous vehicles – and companies would need to charge prices that allowed them to recoup their expensive investments in the technology as well as make a profit. Alternatively, companies that rely on shipping and delivery companies that use driverless technology may be faced with an increase in transportation or shipping costs (variable costs). These costs may be higher because technology is often more expensive when it is new than it will be in the future, when it is easier and more cost effective to produce and also more accessible. A good example of the change in cost of a new technological innovation over time is the personal computer, which was very expensive when it was first developed but has decreased in cost significantly since that time. The same will likely happen over time with the cost of creating and using driverless transportation.

You might wonder why a company would trade variable costs for fixed costs. One reason might be to meet company goals, such as gaining market share. Other reasons include being a leader in the use of innovation and improving efficiencies. If a company uses the latest technology, such as online ordering and delivery, this may help the company attract a new type of customer or create loyalty with longstanding customers. In addition, although fixed costs are riskier because they exist regardless of the sales level, once those fixed costs are met, profits grow. All of these new trends result in changes in the composition of fixed and variable costs for a company and it is this composition that helps determine a company’s profit.

As you will learn in future chapters, in order for businesses to remain profitable, it is important for managers to understand how to measure and manage fixed and variable costs for decision-making. In this chapter, we begin examining the relationship among sales volume, fixed costs, variable costs, and profit in decision-making. We will discuss how to use the concepts of fixed and variable costs and their relationship to profit to determine the sales needed to break even or to reach a desired profit. You will also learn how to plan for changes in selling price or costs, whether a single product, multiple products, or services are involved.

What sort of decisions can be made with CVP analysis?

Once you understand variable costs, fixed costs and CVP – the application to internal decision making is vast. The table below provides some examples.

| Link between Business Decision and Cost Information Used | |

|---|---|

| Decision | Cost Information |

| Discontinue a product line | Variable costs, overhead directly tied to product, potential reduction in fixed costs |

| Add second production shift | Labor costs, cost of fringe benefits, potential overhead increases (utilities, security personnel) |

| Open additional retail outlets | Fixed costs, variable operating costs, potential increases in administrative expenses at corporate headquarters |

Deciding Between Orders

You are evaluating orders from two new customers, but you will only be able to accept one of the orders without increasing your fixed costs. Management has directed you to choose the one that is most profitable for the company. Customer A is ordering 500 units and is willing to pay $200 per unit, and these units have a contribution margin of $60 per unit. Customer B is ordering 1,000 units and is willing to pay $140 per unit, and these units have a contribution margin ratio of 40%. Which order do you select and why?

Watch this video from Investopedia reviewing the concept of contribution margin to learn more. Keep in mind that contribution margin per sale first contributes to meeting fixed costs and then to profit.

Key Concepts and Summary

- Contribution margin can be used to calculate how much of every dollar in sales is available to cover fixed expenses and contribute to profit.

- Contribution margin can be expressed on a per-unit basis, as a ratio, or in total.

- A specialised profit and loss/income statement, the Contribution Margin Income Statement, can be useful in looking at total sales and total contribution margin at varying levels of activity.

Check your understanding

By completing the following activity