Identifying risks to a business using the fraud triangle

Amanda White; Mitchell Franklin; Patty Graybeal; and Dixon Cooper

What is fraud?

A reminder about the definition of fraud that we will be applying:

charged with governance, employees, or third parties, involving the use of deception

to obtain an unjust or illegal advantage.” (ASA240.12(a) emphasis added)

We have added emphasis on certain words because of their importance. Fraud is intentional – someone plans to engage in fraud, and it doesn’t happen by accident. Of course, someone may engage in fraud accidentally one time, but continuing to engage in that behaviour is intentional.

Deception is a key word because it means that the individual (or group of individuals) engaging in the fraud are trying to get the business to believe something that is not correct or not true. And finally the words unjust or illegal advantage are emphasised because it represents the outcome of the fraud – notice that it doesn’t focus just on cash being stolen, but any type of advantage. You might fraudulently over-state how many items you sold as a sales person in a business to be recognised as the top performer for the year. Top performers across the country might receive an overseas conference trip. Or additional annual leave.

Some recent examples of fraud

$4 million worth of salmon (yes – the fish!) was stolen from a Sydney processing plant by employees in December 2020 (Carreon, 2021).

It is alleged that Bill Pappas stole over $500m by setting up a fraudulent scheme involving fake equipment leases. (Chau, 2021)

Detecting fraud in the workplace

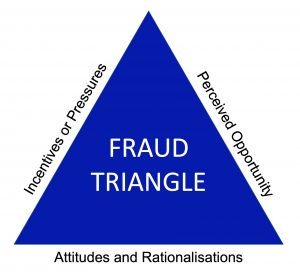

Fraud is not easy to detect and is often identified by anonymous tips or by accident, so many companies use the fraud triangle to help in the analysis of workplace fraud. Donald Cressey, an American criminologist and sociologist, developed the fraud triangle to help explain why law-abiding citizens sometimes commit serious workplace-related crimes. He determined that people who embezzled money from banks were typically otherwise law-abiding citizens who came into a “non-shareable financial problem.” A non-shareable financial problem is when a trusted individual has a financial issue or problem that he or she feels can’t be shared. However, it is felt that the problem can be alleviated by surreptitiously violating the position of trust through some type of illegal response, such as embezzlement or other forms of misappropriation. The guilty party is typically able to rationalise the illegal action. Although they committed serious financial crimes, for many of them, it was their first offence.

The fraud triangle consists of three elements: incentive or pressure, opportunity, and rationalisation and attitudes. Each of the elements needs to be present for workplace fraud to occur.

People have both financial and non-financial incentives to engage in fraud, and there may also be pressures. These could be external (such as financial hardship) or internal (such as wanting to appear to be successful amongst peers). Perceived opportunities may arise in business processes where there is a lack of oversight, checking, confirmation or some other internal control to ensure employees act in the best interest of the business and its owners/shareholders. Opportunities arise because of something called control weaknesses – a lack of a control in a part of the business process where there is a risk of fraud. We’ll get into processes and weaknesses later in this chapter because those working in accounting and accounting information has an important role to play in identifying control weaknesses.

The final component is attitudes and rationalisations. Attitudes are related to our beliefs related to fraud. For example, is an intentional failure to scan an item on purpose at a self-service checkout at the supermarket considered theft or stealing? A rationalisation is an argument someone uses to convince themselves that their fraud is not really fraud at all, that it is acceptable behaviour. An example is an employee who steals cash from a business after they did not receive a promotion, with the claim that they’d “earned” the stolen funds and “deserved” the promotion.

Typically, all three elements of the triangle must be in place for an employee to commit fraud, but companies usually focus on the opportunity aspect of mitigating fraud because, they can develop internal controls to manage the risk. The rationalisation and pressure to commit fraud are harder to understand and identify. Many businesses may recognise that an employee may be under pressure, but many times the signs of pressure are missed.

Virtually all types of businesses can fall victim to fraudulent behavior. For example, chemists desperately searching for Rapid Antigen Tests may purchase fake tests, sports teams requiring players and staff to show COVID-19 vaccination certificates have found fakes, Elizabeth Holmes from Theranos raised and lost a multi billion dollar company based on blood testing technology that actually didn’t work.

Real life example – Theranos

One of the most compelling frauds of recent times is that of Elizabeth Holmes and Theranos. Theranos was hailed as life changing medical technology – testing people for a raft of diseases and health issues with a few drops of blood, instead of multiple vials. Theranos had signed deals with major pharmacy chains to install their machines in stores and trained up thousands of staff. However, the small blood testing machine never worked. How did Holmes get away with taking the investments of big names like Rupert Murdoch? The board of directors trusted their charismatic and charming CEO and her covers on Forbes magazines and others as the next Steve Jobs. As a private company, no audits of their financial statements were ever conducted – the company published figures for revenues and profits that were never checked and ended up being pure fiction. Things only started unravelling when the regulator for companies in the USA (the Securities Exchange Commission) started investigating claims of fraudulent behaviour.

Interested to read more? Jordan Hayne has a comprehensive article on ABC News.

Real life example – UltraColour’s accounts drained by employees

Greg, a small business owner from Sydney’s western suburbs, had $3.7 million stolen from his business over its lifetime by a trusted employee. He had hired the daughter of a friend, Vicki, to manage administration and the accounting in his business. Vicki had access to the bank accounts and accounting system and hid her theft through various accounting transactions. Why did she do it? Vicki claims she was addicted to poker machines and had stolen the money and spent it all. In this case there was a significant opportunity for Vicki to engage in fraud and she had incentive / pressure because of her gambling addiction.

You can read the full story by Steven Cannane on ABC News.

Unfortunately, this is one of many examples that occur on a daily basis. In almost any city on almost any day, there are articles in local newspapers about a theft from a company by its employees. Although these thefts can involve assets such as inventory, most often, employee theft involves cash that the employee has access to as part of his, her or their day-to-day job.

Small businesses have few employees, but often they have certain employees who are trusted with responsibilities that may not have complete internal control systems. This situation makes small businesses especially vulnerable to fraud. The article “Small Business Fraud and the Trusted Employee” from the Association of Certified Fraud Examiners describes how a trusted employee may come to commit fraud, and how a small business can prevent it from happening.

Accountants, and other members of the management team, are in a good position to control the perceived opportunity side of the fraud triangle through good internal controls, which are policies and procedures used by management and accountants of a company to protect assets and maintain proper and efficient operations within a company with the intent to minimise fraud. An internal auditor is an employee of an organisation whose job is to provide an independent and objective evaluation of the company’s accounting and operational activities. Management typically reviews the recommendations and implements stronger internal controls.

Another important role is that of an external auditor, who generally works for an outside public accounting firm that conducts audits and other assignments, such as reviews. Importantly, the external auditor is not an employee of the client. The external auditor prepares reports and then provides opinions as to whether or not the financial statements accurately reflect the financial conditions of the company, subject to the Australian Accounting Standards (AASBs). Professionally certified accountants and external auditors must also comply with a Code of Ethics. The International Ethics Standards Board for Accountants (IESBA) issues an internationally recognised and adopted Code of Ethics. This makes accounting a truly global profession where the standards for accountants are the same in Australia as Zimbabwe or Brazil or Germany or South Korea.

One of the issues faced by any business is that internal control systems can be overridden and can be ineffective if not followed by management or employees. The use of internal controls in both accounting and operations can reduce the risk of fraud. In the unfortunate event that an business is a victim of fraud, the internal controls should provide tools that can be used to identify who is responsible for the fraud and provide evidence that can be used to prosecute the individual responsible for the fraud. This chapter discusses internal controls in the context of accounting and controlling for cash in a typical business setting. These examples are applicable to the other ways in which an business may protect its assets and protect itself against fraud.

Practice question

References

Carreon, B. (2021), Five charged in multimillion-dollar salmon theft scheme. Seafood Source. website link accessed 28 January 2022.

Chau, D. (2021), Bill Papas’s companies earned $500 million from fraud, liquidators allege. ABC news. website link accessed 28 January 2022.

Glossary

- external auditor

- generally works for an outside public accounting firm and conducts audits and other assignments, such as reviews

- fraud

- “an intentional act by one or more individuals among management, those charged with governance, employees, or third parties, involving the use of deception to obtain an unjust or illegal advantage.” (ASA240.12(a))

- fraud triangle

- concept explaining the reasoning behind a person’s decision to commit fraud; the three elements are perceived opportunity, attitudes and rationalisation, and incentive and/or pressure

- internal auditor

- employee of an organisation whose job is to provide an independent and objective evaluation of the company’s accounting and operational activities