Sustainability as part of accountability and organisational reporting

Leanne Gaul

“Sustainaiblity is here to stay or we may not be.” Niall FitzGerald, Co-Chairman of Unilever

Introduction

Sustainability reporting is a relatively new concept when compared with traditional accounting methods evidenced in Mesopotamia, 6000 years ago1.Increasing legislative, taxation and economic influences commencing from the industrial revolution in the 19th century have brought about iterative development of accounting and reporting policy.2 This development seeks to bring together evolving stakeholder needs and expectations and organisational performance.3

Numerous sustainability reporting terms have developed over time such as; corporate social responsibility (CSR) reporting, triple bottom line (TBL) reporting, corporate sustainability and social responsibility (CSSR) reporting, environment, social and governance (ESG) and corporate citizenship reporting.4 The evolution of these terms has led to them being used interchangeably, however this is incorrect, each of these names provide differing context, however ‘sustainability reporting’ encapsulates the spirit of all terms and will be used for the remainder of this chapter.

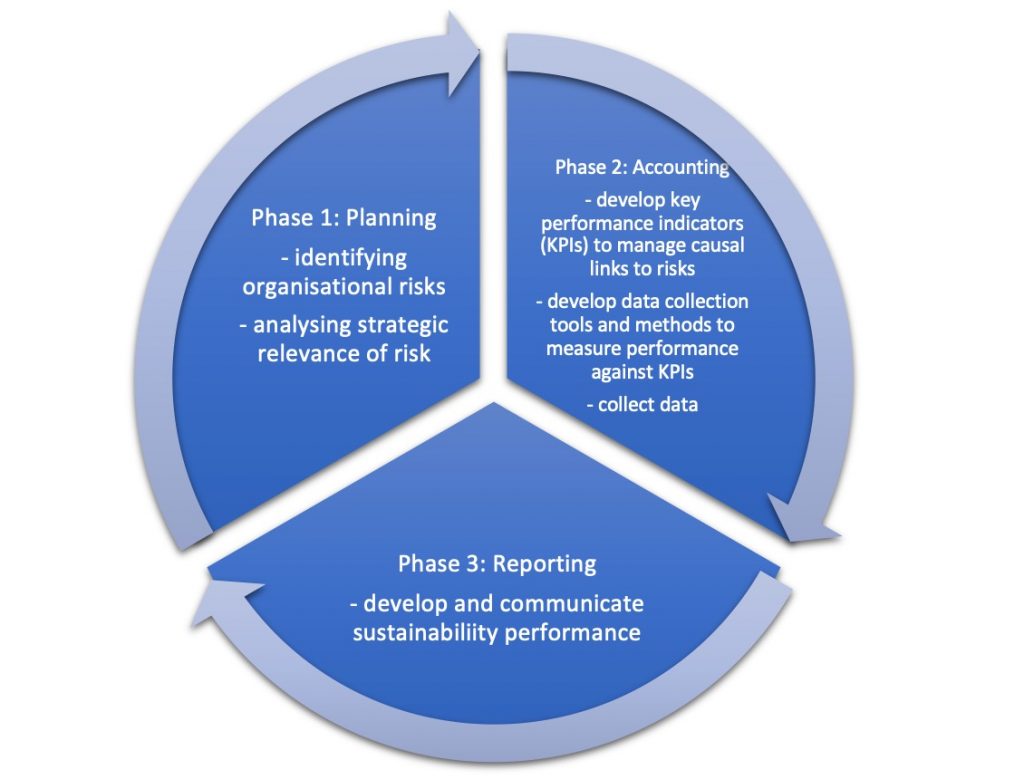

In more recent times the effects of climate change have escalated environmental disasters resulting in increased stakeholder concerns and a call for greater transparency over environmental and social impacts caused by organisational operations.5 The mechanism for accountability is provided through sustainability reporting, however these disclosures are an outcome to the policies and practices implemented by organisations, hence reporting should be viewed as a process of planning, accounting and reporting.6 As this process occurs on a regular basis it is recognised as the sustainability reporting cycle.7 Each phase provides important contributions to the effectiveness of sustainability performance and reporting outcomes, as summarised in diagram 1 below.

Sustainability Reporting Phase 1 – Planning

This phase requires the identification of sustainability risks to the organisation and pinpointing the most strategically relevant risk.9 Issues in the planning phase are motivated by the sustainability strategy, which is driven by the organisations mission, vision, goals and objectives, hence communicating an understanding what of sustainability is to employees and stakeholders becomes crucial. Absence of a clear definition can translate to stakeholder confusion over what is considered sustainable activity and what is not.

The most widely accepted definition was developed by the World Commission on Environment and Development in 1987 in their seminal “Our Common Future” report (or the “Brundtland Report”).10 The Brundtland Report focussed on sustainable development to offset rising negative impacts to social and environmental systems triggered by organisational activities. The writers of the report sought to convey the importance of action to combat the effects of climate change, hence sustainable development was conceived as development that “meets the needs of the present without compromising the ability of future generations to meet their own needs”.11 The concept of ‘future generations’ as stakeholders was previously not considered due to their lack of existence in a present context which did not allow for the possibility of engagement12. Several issues have been associated with this definition including the broadness of scope, the concept of ‘needs’13 and the lack of attention to basic sustainability concepts of social and environmental concerns. This diminished specificity has allowed organisations to adapt sustainability definitions to suit their goals and objectives, such as a skewed approach to financial objectives rather than a balanced approach to economic, social and environmental concerns14. To overcome this issue, adaptations of sustainability definitions have been developed since 198715, however none have been widely accepted nor are they as readily recognisable as the Brundtland Report’s contribution.16

Another important contribution came from John Elkington in 1997, which was developed as a result of the increasing environmental disasters in the 1990s.17 Elkington focussing on three main areas for sustainability disclosure; economic, social and environmental matters and called this Triple Bottom Line (TBL) reporting its focus on profit, people and planet (the 3P’s).18 TBL required a synthesis of all three elements incorporating the traditional financial reporting with environmental and social matters. This enabled insights into each of these three sustainability capitals, but also highlighted relationships between the 3P’s. Why is this important? It allows the user of the TBL report to understand the impact each capital has on the others, that is how do profit-seeking activities impact the environment and society. The increased scope of TBL reporting increases organisational transparency and accountability to stakeholders. For organisations pursuing the TBL approach the mission and business strategy must reflect this concept and identifying appropriate definitions to frame this pathway must be undertaken. Let’s look at Cisco’s mission statement below:

“Shape the future of the Internet by creating unprecedented value and opportunity for our customers, employees, investors, and ecosystem partners.”19

Interpreting this mission statement through the TBL lens (3P’s) identifies:

- Profits – relate to investors;

- People – relate to customers and employees; and

- Planet – relate to ecosystem or environment.

From an inter-relational perspective:

unprecedented value and opportunity – are not only possible for each stakeholder group, but can also be realised through connections. For example: value and opportunities created for employees in the form of improved skills through better training results in a more efficient workforce which improves profits and drives innovations to reduce impact on the environment.

Teaching resource:

The Woolworths Group – People, Planet, Prosperity – http://crs.woolworthsgroup.com.au/

Sustainability Reporting Phase 2 – Accounting

Once risks are identified and analysed in the planning phase, organisational managers can then seek to locate the causal relationship between the sustainability issue and business activities in the accounting phase.20 Once determined, sustainability targets, KPIs, practices and activities can be developed and implemented.21 Let’s look at some examples taken from Pinna et al. (2018) who examined sustainability KPIs from two soft drink companies22 :

| Sustainability Category | KPI | Description/measurement |

| Water and energy (environmental) | Efficiency in water consumption | Number of litres of water required to produce one litre of beverage |

| Efficiency in energy consumption | Energy used per litre of produced beverage | |

| Emissions to water | Measures nutrients and organic pollutants and metal emissions | |

| Emissions (environmental) | Emission to land | Measures oil and coolant consumption, restricted substances intensity and metal emissions |

| Emission to air | Measures air acidification, dust and particles, transport and greenhouse gases | |

| General aspects (social) | Employee turnover | Measures the level of turnover in a company, in terms of number of employee departures divided by the average number of staff members employed. |

Source: Pinna et al. (2018), p. 86523

From a sustainability perspective we can understand the risks to environmental and social perspectives from the given KPIs. The organisations have set a sustainability strategy incorporating impacts to the environment and social concerns, they have identified KPIs that meet with the strategy and set appropriate measurements through policies and practices. Once this has been done appropriate targets would need to be set and then data would be gathered through the relevant period, calculated according to the prescribed formula, then compared to the target. If the organisation outperformed its target a positive message would be communicated to the market, however if it underperformed the opposite may hold. We can see from this the greater level of transparency could put the organisation at a disadvantage, so why would an organisation produce a sustainability report?

The answer is simple, because it is what stakeholders are demanding. In recent times those organisations that have continued to operate sustainably and provide sustainability reporting, have maintained higher stock prices and lower volatility than non-participating entities24. Therefore greater transparency over sustainability matters has inspired greater confidence in investors driving perceived value. So how do organisations account for sustainability?

To account for sustainability performance, formalised frameworks provide a mechanism to maintain quality and standardisation of accounting practices. As accountants we know mandatory compliance with the Australian Accounting Standards is required for the general-purpose financial reports25, however a significant proportion of sustainability reporting is voluntary.26 From a mandatory reporting perspective, the Corporations Act 2001(Cth) provides prescriptive guidance for financial reporting which incorporates the requirement to comply with accounting standards.27 Materiality plays an important role in financial reporting disclosure which relates to information that has a material effect on price or value of the organisation and consequently results in misstatement or non-disclosure causing adverse actions by users of the report.28 Despite the material impact of non-financial activities by companies29, Australian government has not made the move to require companies incorporate environmental and social matters within or supplementary to the compulsory financial reporting.30 An exception is the National Greenhouse and Energy Reporting (NGER) scheme initiated by the National Greenhouse and Energy Reporting Act 2007 (Cth) which is a national framework providing guidance to companies reporting on their greenhouse gas emissions, energy production and consumption and other similar information.31

To meet the requirements of disclosure, whether mandatory or voluntary, performance measurement systems must be developed and implemented. The purpose of standard approaches to measuring organisational performance is to achieve comparable and complete reporting with the objective of being transparent in operational activities.32 Therefore the development of universally accepted standards and frameworks is critical.33 To support the development of non-financial standard-setting, numerous international frameworks have made contributions over time, three of which will be discussed below commencing with the most well-known provider the Global Reporting Initiative or GRI.

The GRI, established by the Coalition for Environmentally Responsible Economies (CERES) in 1997, is an independent body that provides organisations with standards to disclose sustainability impacts, thus improving communications efficacy.34 The GRI standards are split into three categories; topic, sector and universal.35 Another global standards provider is AccountAbility offering guidance over three core areas; AA1000AP-guidance for organisational response to sustainability concerns and long-term development; AA1000SES stakeholder engagement and AA1000AS v3 relating to sustainability assurance.36 A final consideration was developed by the International Organization for Standardization (ISO) commencing in 1947.37 ISO is a collaborative association facilitating the sharing of knowledge by experts to develop standards.38 The ISO standards encapsulate a broad scope of sustainability issues in order to support global trade, economic growth, innovation, health and safety and sustainable development.39

The three standard-setters discussed in the previous paragraph are only a small selection of the available offerings, however they widely used in the global context. All three standards are offered on an international scale allowing standardisation of reporting and fostering comparability between organisations, industries, markets and geographical regions.40 It is important to note, organisations can use numerous standards from various standard-setters, this provides flexibility for organisations to select appropriate standards to support sustainability goals and objectives.

Additional resources

- for additional insights into sustainability reporting guidance and other tools see: Siew, R. Y. J. (2015). A review of corporate sustainability tools (SRTs). Journal of Environmental Management, 164, (pp. 180-195) – https://doi. 10.1016/j.jenvman.2015.09.010

Sustainability Reporting Phase 3 – Reporting

Beyond the planning and accounting phases follows reporting for accountability to internal and external stakeholders. Two main forms of reporting will be considered below: (1) stand-alone reporting and (2) integrated reporting (<IR>):

- (1) Stand-alone sustainability reporting – is set apart from the traditional annual report (AR), usually as an addendum to the AR or separate entirely. This method fails to consider the relationships between environmental, social and economic concerns.41 This type of reporting is developed by the organisation, either internally or through associations such as consultants or best practice.

- (2) Integrated reporting (<IR>) – has the potential to overcome the limitations of stand-alone reporting. The integrated report incorporates economic, social and environmental performance, not only meeting legislative and regulatory compliance, but also providing insights into the connections or relationships between all three reporting areas.42 This supports the TBL concept. <IR> was introduced by the International Integrated Reporting Council (IIRC) and is a global partnership comprising of regulators, investors, business and academic stakeholders, accounting professionals and non-government organisations (NGOs).43 <IR> is a framework for reporting, it does not provide standards such as those offered by GRI. Rather it provides a mechanism to nurture ‘integrated thinking’ by and organisation to encourage all business units to set and maintain sustainability goals.44*

The iterative development of sustainability reporting has created a dynamic environment, which continues in its state of flux. Movement toward integrated reporting has been growing since 2000, however stand-alone reporting continues to hold favour with a majority of Australian listed companies preferring this method, as discussed in the following section.

Additional resources

For more reading on concepts discussed in this section click on the links provided below:

- Integrated reporting website: https://www.integratedreporting.org/

- *Integrated thinking: A virtuous loop – https://www.integratedreporting.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/06/Integrated-thinking-virtuous-loop.pdf

- Integrated reporting examples: http://examples.integratedreporting.org/home

- Stand-alone sustainability report example: APA sustainability report 2021 – https://www.apa.com.au/globalassets/asx-releases/2021/apa-sustainability-report-fy21.pdf

- M. Bray & M Chapman, What does an integrated report look like? https://home.kpmg/content/dam/kpmg/pdf/2013/04/what-does-ir-look-like.pdf

How common is Sustainability Reporting?

The KPMG Sustainability Reporting Survey 2020 (the survey) investigates the incidence of sustainability reporting from a global perspective. The survey identified 96 percent of the G250 companies45 and 80 percent of the N100 companies46 produced sustainability reports. Additionally, 76 percent of the G250 companies incorporate sustainability performance information in their annual reports47, thus aligning with an integrated reporting presentation. The Australian sustainability reporting environment includes both mandated and voluntary forms, predominantly the latter. Due to the voluntary nature of most reporting, managerial discretion over sustainability reporting content results in a failure to meet stakeholder reporting expectations.48 Despite this, Australian companies producing sustainability disclosures continue to grow with 98 percent of ASX100 companies publishing reports, increasing from 93 percent in 2017. Those companies taking a more integrated approach to sustainability reporting increased from 29 percent (2017) to 67 percent (2020), indicating a shift in favour of organisations embedding sustainability goals into business processes.49

Sustainability stakeholders

The purpose of organisations producing sustainability reports is to communicate organisational sustainability performance50, as such it is important managers select voluntary sustainability content based upon external stakeholders’ information needs. Increasingly stakeholders are playing greater roles in the evolution of sustainability reporting from a global perspective.51 Common stakeholder groups are employees, customers, regulators, investors, government, communities, indigenous groups, society or the broader public, suppliers and NGOs. Stakeholders not commonly cited are transient populations (such as holidaymakers/tourists)52, future generations53 and natural ecosystems/biodiversity.54 The latter two cannot self-represent their interests, hence they require qualified representation.55

Organisational managers are required to prioritise competing stakeholder needs due to their limited resources. This may result in some stakeholders only having their needs partly met or not at all. Therefore, effective engagement by managers involving two-way communications will provide more informed decisions and increase transparency and effectiveness of reporting.

Self-study task

You work for an Australian energy company – products are a mixture of coal fired and renewable energy and LPG. List organisational stakeholders and rank in order of most important to least important and provide a short explanation for each.

Concluding remarks

Escalating global natural disasters from climate change is stimulating stakeholder demand for companies to operate sustainably and be accountable for social and environmental impacts from business operations. Hence public and private sectors are producing sustainability reports to retain, and attract, customers, investors and suppliers. The process of producing these reports is time and resource intensive, however outcomes are beneficial to all participants as organisations foster closer relationships with their stakeholders and build greater efficiencies in business operations. The sustainability reporting cycle is continuously developing, incorporating innovative development and improvement to best practice, thus organisations, and other stakeholders, must keep working toward the goal of sustainable development. To sum up with a quote from Edmund Burke:

“Nobody made a greater mistake that he (or she) who did nothing because he (or she) could only do a little.”

From a sustainability perspective, the key take-away from this quote is individuals can make small contributions to offset environmental degradation, poverty and social injustice and these small efforts will cohesively generate significant change for the greater good. This provides context to “Think globally, act locally”.

Footnotes

- M.R. Mathews, Socially responsible accounting, Routledge & Chapman, London, 1984.

- ibid

- ibid

- M. S. Urdan & P. Luoma, ‘Designing effective sustainability assignments: How and why definitions of sustainability impact assignments and learning outcomes’, Journal of Management Education, 44(6), (794-821), 2020.

- I. Herremans, Sustainability performance and reporting, Business Expert Press, New York, 2019. For current information on the impacts of climate change see website: Climate Change in Australia – https://www.climatechangeinaustralia.gov.au/en/

- S. Schaltegger & M. Wagner, ‘Managing sustainability performance measurement and reporting in an integrated manner: Sustainability accounting as the link between the sustainability balanced scorecard and sustainability reporting’, Sustainability Accounting and Reporting, Springer, Netherlands, 2006.

A. Kaur & S. Lodhia, ‘Stakeholder engagement in sustainability accounting and reporting: A study of Australian local councils’,Accounting, Auditing, & Accountability, Emerald Group Publishing Ltd, 31(1), (338-368), 2018. - ibid

- S. Schaltegger and M. Wagner, ‘Managing sustainability performance measurement and reporting in an integrated manner: Sustainability accounting as the link between the sustainability balanced scorecard and sustainability reporting’ in S. Schaltegger, M. Bennett and R. Burritt (eds) Sustainability Accounting and Reporting, Springer, Delft, Netherlands, 2006, ch 30.

- ibid

- M. S. Urdan and P. Luoma, ‘Designing effective sustainability assignments: How and why definitions of sustainability impact assignments and learning outcomes’(2020) 44(6) Journal of Management Education 794-821.

- World Commission on Environmental Development, Report for the World Commission on Environment and Development: Our Common Future. https://sustainabledevelopment.un.org/content/documents/5987our-common-future.pdf p. 17 (accessed 5 January 2022).

- M. A. White, ‘Sustainability: I know it when I see it’ (2013) 86 Ecological Economics 213-217.

- ibid

- P. Johnston, M. Everard, D. Santillo and K. H. Robert, ‘Reclaiming the definition of sustainability’, (2007) 14(1) Environmental Science and Pollution Research International 60.

H. Alhaddi, Triple bottom line and sustainability: A literature review’ (2015) 1 Business and Management Studies. - M. S. Urdan and P. Luoma, ‘Designing effective sustainability assignments: How and why definitions of sustainability impact assignments and learning outcomes’ (2020) 44(6) Journal of Management Education 794-821.

- S. Roostaie, N. Nawari and C. J. Kibert, ‘Sustainability and resilience: A review of definitions, relationships, and their integration into a combined building assessment framework’ (2019) 154 Building and Environment 132-144.

- J. Elkington, ‘Accounting for triple bottom line’ (1997) 2(3) Measuring Business Excellence 18-22).

- ibid

- A. Miteva. Business strategy: 101 incredible mission statement examples (in 2022), https://mktoolboxsuite.com/mission-statement-examples/, 2022 (accessed 9 January 2022).

- S. Schaltegger and M. Wagner, ‘Managing sustainability performance measurement and reporting in an integrated manner: Sustainability accounting as the link between the sustainability balanced scorecard and sustainability reporting’ in S. Schaltegger, M. Bennett and R. Burritt (eds) Sustainability Accounting and Reporting, Springer, Delft, Netherlands, 2006, ch 30.

- ibid

- C. Pinna, M. Demartini, F. Tonelli and S. Terzi, ‘How soft drink supply chains drive sustainability: Key performance indicators (KPIs) identification’ (2018) 72 ScienceDirect 862-867.

- ibid

- R. Albuquerque, Y. Koskinen, S. Yang and C. Zhang, Resiliency of environmental and social stocks: An analysis of the exogenous COVID-19 market crash. (2020) 9(3) The Review of Corporate Finance Studies 593-621.

- Corporations Act 2001 (Cth) s 296

- Parliamentary Joint Committee on corporations and Financial Services, ‘Chapter seven – Sustainability report: Current and legislative market requirements’ https://www.aph.gov.au/Parliamentary_Business/Committees/Joint/Corporations_and_Financial_Services/Completed_inquiries/2004-07/corporate_responsibility/report/c07 (accessed 7 January 2022).

- Parliamentary Joint Committee on corporations and Financial Services, ‘Chapter seven – Sustainability report: Current and legislative market requirements’ https://www.aph.gov.au/Parliamentary_Business/Committees/Joint/Corporations_and_Financial_Services/Completed_inquiries/2004-07/corporate_responsibility/report/c07 (accessed 7 January 2022).

- Australian Accounting Standards Board, ‘AASB 1031: Materiality’ https://www.aasb.gov.au/admin/file/content102/c3/AASB1031_9-95.pdf (accessed 7 January 2022).

- Corporations Act 2001 (Cth) s. 677

- Parliamentary Joint Committee on corporations and Financial Services, ‘Chapter seven – Sustainability report: Current and legislative market requirements’ https://www.aph.gov.au/Parliamentary_Business/Committees/Joint/Corporations_and_Financial_Services/Completed_inquiries/2004-07/corporate_responsibility/report/c07 (accessed 7 January 2022).

- Clean Energy Regulator, ‘About the National Greenhouse Energy Reporting scheme’ (n.d.) http://www.cleanenergyregulator.gov.au/NGER/About-the-National-Greenhouse-and-Energy-Reporting-scheme (accessed 7 January 2022).

- S. Schaltegger and M. Wagner, ‘Managing sustainability performance measurement and reporting in an integrated manner: Sustainability accounting as the link between the sustainability balanced scorecard and sustainability reporting’ in S. Schaltegger, M. Bennett and R. Burritt (eds) Sustainability Accounting and Reporting, Springer, Delft, Netherlands, 2006, ch 30.

- ibid

- Global Reporting Initiative, ‘How are we funded’, https://www.globalreporting.org/about-gri/how-we-are-funded/, 2021. Siew, R. Y. J. (2015). A review of corporate sustainability tools (SRTs). Journal of Environmental Management, 164, (pp. 180-195) – https://doi. 10.1016/j.jenvman.2015.09.010

- Global Reporting Initiative, ‘GRI standards: A short introduction to the GRI standards’, https://www.globalreporting.org/media/wtaf14tw/a-short-introduction-to-the-gri-standards.pdf, n.d. (accessed 7 January 2022).

- AccountAbility, ‘Standards’. https://www.accountability.org/standards (accessed 7 January 2022).

- International Organization for Standardization, ‘Developing standards’, https://www.iso.org/developing-standards.html (accessed 7 January 2022).

- ibid

- International Organization for Standardization, ‘9000Store: Who is ISO?’ https://the9000store.com/articles/who-is-iso/ (accessed 7 January 2022).

- Global Reporting Initiative, ‘The importance of these standards’, https://www.globalreporting.org/standards/standards-development/universal-standards/ (accessed 7 January 2022). G. Michalczuk, and U. Konarzewska, (2018, 26-27 September 2018), ‘GRI reporting framework as a tool of social accounting [Paper presentation]’, Economic and Social Development: 33rd International Conference on Economic and Social Development – “Managerial Issues in Modern Business”, Warsaw.

- J.C. Jensen and N. Berg, ‘Determinants of traditional sustainability reporting versus integrated reporting: An institutionalist approach’. (2012) Business strategy and the environment, 21(5), 299-316. https://doi.org/10.1002/bse.740

- International Integrated Reporting Council. (2021). International <IR> framework. https://www.integratedreporting.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/01/InternationalIntegratedReportingFramework.pdf (accessed 7 January 2022).

- ibid

- T. Feng, L. Cummings and D. Tweedie, ‘Exploring integrated thinking in integrated reporting – an exploratory study in Australia’ (2017) 18(2) Journal of intellectual capital. 330-353.

- G250 is the top global 250 companies

- N100 includes 5,200 companies from 52 countries

- KPMG, ‘The time has come: Australian supplement global sustainable reporting survey (11th ed.)’ https://assets.kpmg/content/dam/kpmg/au/pdf/2020/sustainability-reporting-survey-2020-au-supplement.pdf (accessed 7 January 2022).

- R. L. Burritt & S. Schaltegger, ‘Sustainability accounting and reporting: Fad or trend?’ (2010) 23(7) Accounting, Auditing & Accountability 829-846.

- KPMG, ‘The time has come: Australian supplement global sustainable reporting survey (11th ed.)’ https://assets.kpmg/content/dam/kpmg/au/pdf/2020/sustainability-reporting-survey-2020-au-supplement.pdf. (accessed 7 January 2022).

- R. Lozano and D. Huisingh, ‘Inter-linking issues and dimensions in sustainability reporting’ (2011) 19(2) Journal of Cleaner Production 99-107.

- A. Uyar, ‘Stand-Alone Sustainability Reporting Practices in an Emerging Market: A Longitudinal Investigation’ (2017) 28(2) Journal of Corporate Accounting & Finance (Wiley) 62–70.

- A. Kaur and S. Lodhia, S. ‘Stakeholder engagement in sustainability accounting and reporting: A study of Australian local councils’ (2018) 31(1) Accounting, auditing, & accountability 338-368.

- World Commission on Environmental Development. Report for the World Commission on Environment and Development: Our Common Future. https://sustainabledevelopment.un.org/content/documents/5987our-common-future.pdf (accessed 6 January 2022).

- S. Gaia and M. J. Jones, ‘UK local councils reporting of biodiversity values: A stakeholder perspective’ (2017) 30(7) Accounting, Auditing & Accountability Journal 1614-1638.

- ibid